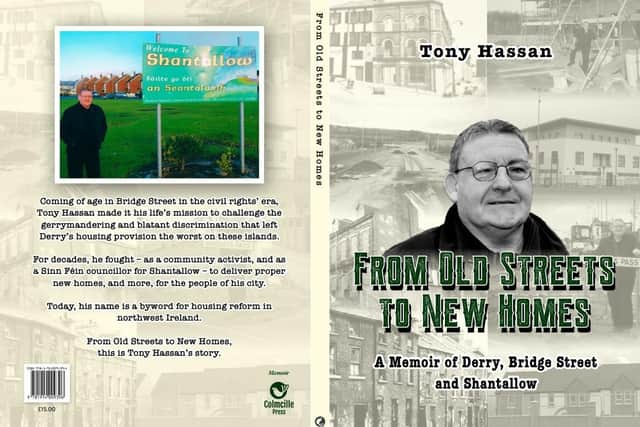

'From Old Streets to New Homes: A Memoir of Derry' by Tony Hassan: Working Days

and live on Freeview channel 276

Working Days

When I left school around Easter time in 1960, my first job was as a message boy in Harry Doherty’s shop in Creggan. For the sum of £1.50 per week I had to deliver groceries in and around the Creggan area and I loved it. It was a great job, and the shop was always full of people. I met so many interesting folk in the six months I worked there, and I learned so much about life. If I wasn’t delivering groceries, then I was bagging spuds or serving in the shop itself.

I remember once delivering groceries in the middle of what we called Hurricane Debbie. I was blown totally off the bike by the winds, and all the groceries I was supposed to be delivering were thrown all over the place too. That was an experience! On the whole, Harry Doherty was well known for doing a lot of good work ensuring the people of Creggan and beyond had what they needed to survive. He was a massive sports-fan too and a boxing promoter for a time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

When I left Harry Doherty’s shop, I got an interview for the Birmingham Sound Reproducers (BSR) Factory in Derry’s Bligh’s Lane. At that time, the BSR was one of the major employers for men in the city and its factory made parts for record players.

I started in the BSR Factory in November 1961, and I felt this was a job to be proud of. My first wage with them was £2.60 per week back then, which rose to nearly £4.00 per week if we worked overtime.

We worked on the conveyor belt, putting the motors on the record players. It was a job we were expected to be speedy at, and it was often hard to fathom. My sidekick on the opposite side of the belt was Joe Doherty, a fellow Bridge Street native, and he often helped me keep pace with the workload. Another friend worked there, too - Danny Crerand. He was actually an inspector for the factory.

While I was at the BSR, there were several serious disputes to deal with, and two pay-offs within the company. I was given redundancy in the first wave of pay-offs but was later brought back after three months.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

After that, the factory introduced a new tape recorder in the system and required staff to work the lines again. I agreed to work the line, putting the motors on the new record-playing machines, and my sidekick at that time was a man called Colum Norris.

The factory finally closed its doors in 1967, putting almost 2,000 people out of work across the city of Derry and devastating the male workforce. That was such a sad time for Derry, with so many men women and boys forced to claim the dole at the time just to make ends meet.

After the BSR, I was out of work for around a month when we heard that a new factory was coming to Derry, and it needed volunteers to go over to England to train. I inquired at the dole office in Derry and got an interview for one of these new positions.

The new job was at the LEC Refrigeration Company, who had built a new factory at Maydown, but were originally based at Bognor Regis in England. In total, 22 Derry trainees were flown to England for training. We were each told that the conditions and wages of this new job were exceptionally good, which we were pleased about to be honest. Management put us all up for two weeks in a Butlin’s holiday camp, until they managed to get accommodation for us all in England. The company, LEC, made fridges and fridge freezers and their new factory was nearing completion in Derry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

As we trained up in England, we were informed that the factory in Derry was almost completed. I was trained in bench-fitting and drilling, and the working conditions were not bad. The wages were better than the BSR, too, and with a bit of overtime we heard that workers could earn as much as £35 a week.

I worked there for five months until August 1968, when I went back to Derry. I arrived back on August 12,1968, and after getting home I met some friends who told me about another new factory in Maydown, Towler Hydraulics, who were looking for bench-fitters.

The next morning, I went down to this new factory and asked to see someone. A man called Stan Pye came out and introduced himself as Foreman of the plant, and I told him that I was looking for a job and had just come back from working in England. After a brief discussion, he asked when I could start, and I said now - so I got the job.

Towler Hydraulics specialised in the manufacture of high-pressure oil hydraulic pumps for the oil industry, and they were looking for bench-fitters and drillers. They had two shift policies in the factory, and Towlers operated on piecework, which means you were paid based on how much work you did. It was the best job I ever had, and the conditions were great. The money was very good, too, and you could earn £80 or 90 in your hand a week if you were lucky. If your workload was not finished, you were paid a percentage of what was done when the job was finished and the rest as a bonus.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

Sadly, that factory was affected by the same saga that always hits Derry. The factory ran into difficulty and began paying people off, including me. In 1972, the Derry factory eventually closed, and operations went back to its parent factory in Leeds. After Towlers, I got a job at Regna International in Springtown industrial Estate. They made cash registers, and I worked there for two years until 1974, assembling parts for the cash registers.

From then on, I was unemployed for three months and a friend of mine, Davey Collins, asked me to give him a lift down to Maydown for an interview in Hutchinson Yarn Factory (Courtaulds Group). Of course, I drove him down to the factory and waited for him while he went for his job interview. I knew the personnel manager at this factory, Eamon Nolan, and I had asked Davey to tell Eamon that I was looking for a job.

While I sat there in the car at the gate house for Davey to finish his interview, Eamon Nolan called the gate-man and told him to send me up for an interview, too. He offered me a job in the warehouse, starting the next day. I accepted.

The job consisted of loading heavy, forty-foot containers and then stacking the boxes of yarn as they came off the conveyor belt into pallets.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe craic was great, and the Foreman, Jerry Sharkey, had worked with us previously in the BSR Factory. We worked with such a great bunch of lads, including the O’Brien brothers, big John Traynor, John Nash, Danny Gallagher and Leo Macari. Looking back, I have to say that I looked forward to going to work in those days. Leo was a brilliant colleague to work with, as were all the others.

Like so many other factories in Derry over the years, Hutchinson Yarn Factory eventually ran into difficulty and closed its doors in November 1979. Once again, I was out of a job and unsure of which direction to take next. Jobs were scarce, and though I applied to several, I got nowhere. Perhaps because I was a member of Sinn Féin. I applied for several jobs unsuccessfully, and it was around then that I decided to work full-time for the party.

‘From Old Streets to New Homes: A Memoir of Derry, Bridge Street and Shantallow’ (Colmcille Press) is out now, priced £15.