A son of Moville, the US Army and a mother's World War I agony

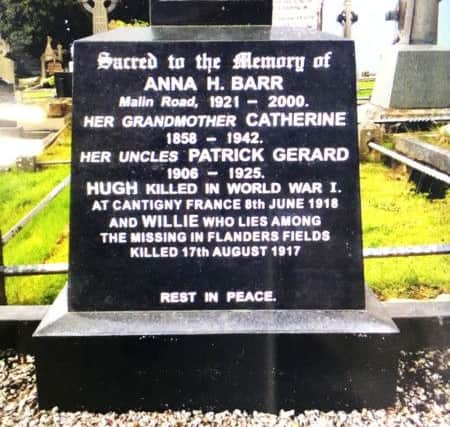

I, along with my brothers Harry and Ciaran, will attend the centenary commemoration of the Battle of Cantigny. There, in a small French village, we will honour the memory of both American and German soldiers, and, in particular, our granduncle, Private Hugh Barr, Company G, 26th Infantry Regiment, United States Army.

It was around midday on Saturday, October 3, 1914, when Hugh Barr, a young man of twenty years, suitcase in hand, stepped out the front door of his home on the Malin Road in Moville. His mother, Catherine, and his younger brother, Willie, wept. Harry, his older brother, in charge of the family tailoring business since the untimely death of their father in 1911, was more composed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJust over seven years later, Hugh’s remains would be carried through that same front door.

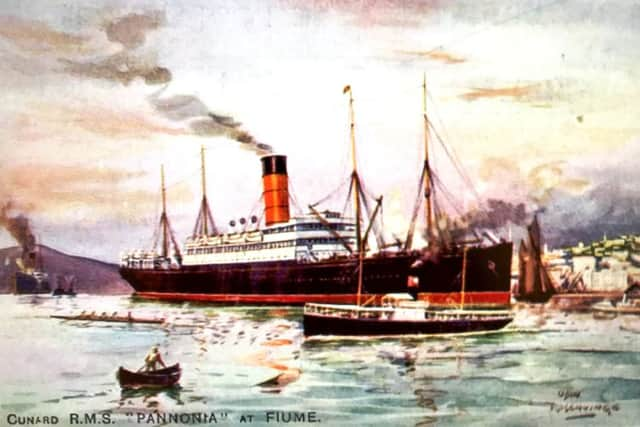

As he strode down the Icehouse Brae, the ‘Pannonia,’ anchored in Lough Foyle, came into view, its red funnel spewing black smoke into a blue sky. One of the smaller ocean liners, with accommodation for forty first class and eight hundred third class passengers, it had arrived earlier in the day from Glasgow. Hugh walked along the crowded stone pier and jostled his way onto a paddle tender that would transport him out to the ship. A similar scene was unfolding on a pier up-river in Derry.

At 4.30pm, with darkness descending, the ‘Pannonia’ weighed anchor and slowly sailed out into the Atlantic Ocean on its ten-day voyage to New York. Standing on the deck, Hugh forlornly stared at the lights of Moville fading into the distance.

The old world he was leaving behind was in a sorry state. Opposing armies were bogged down in horrific trench warfare that would tragically touch the lives of many families in Ireland. With the suspension of Home Rule until after the war, John Redmond’s hopes had been squashed. Even so, the leader of the Irish Party was grateful. He urged young Irish men to go ‘wherever the firing line extends.’ In those first months of that bloody struggle, 50,000 of them volunteered in the King’s army. Others, however, were planning a different future for Ireland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe new world that Hugh entered, as he passed through Ellis Island and out onto the bustling streets of New York City, was profiting from the turmoil in Europe. The British and French, to keep the carnage going, needed all the implements of war that a ‘neutral’ America could provide. Bullets and guns, poison and barbed wire, horses and mules, wheat and cotton. The owners of chemical plants and steel mills and arms factories, along with farmers and workers were only to happy to help. Exports surged, wages rose and Hugh Barr found work at the Brooklyn Railyard.

For the next two and a half years, President Woodrow Wilson kept America out of the war. That changed in early 1917 when Germany recommenced unrestricted submarine attacks. Kaiser Wilhelm II gambled that, if his navy could sink enough ships, American ones included, carrying goods to Britain and France, the allies would be forced to sue for peace before America could mobilise and transport soldiers to Europe. That was a mistake and the Kaiser made it worse when he ordered his foreign minister to send a telegram to the German Embassy in Mexico with instructions to entice that country to invade the United States. The promised reward was the return to Mexico of the lost territories of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. The telegram was intercepted and released to the Press. The American public was incensed. The President went to Congress to request a vote for war. Congress obliged and, on Good Friday, April 6, 1917, America declared war on Germany.

That old world Hugh had left behind was fast encroaching on his new life in America. On a mild Spring evening in May, 1917, as he walked home from work along Bedford Avenue in Brooklyn, to his lodgings at number 445, there was a letter waiting for him. It contained instructions for conscription into the army. All male citizens age 21 to 30, as well as immigrants who had submitted citizenship papers, were ordered to line up on Tuesday, June 5, to register. Hugh, not yet a citizen, stated that he was the sole provider for his widowed mother back in Ireland. That should have earned him a deferment with a good chance that, by the time he was drafted, the war would be over. But he didn’t wait to be called up. He volunteered.

Perhaps he felt guilty that, while he was safe and sound in New York, his younger brother, Willie, along with his cousin, Arthur Murphy, had left Moville in 1915 and gone over to Greenock in Scotland to enlist in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers? Maybe it was the opportunity for travel and adventure and, perhaps, the chance to meet up with Willie? Whatever the reason, Catherine Barr now had two sons in the war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile Hugh toiled through boot camp, across the ocean in Belgium a massive bombardment had roared into life, signalling the start of the Third Battle of Ypres. It would come to be known as Passchendaele and Willie and Arthur were in the thick of it. At dawn on Thursday, August 16, 1917, they went over the top and the Germans opened up with their machine guns. Arthur survived. Willie disappeared into the mud of Flanders fields never to be found.

As darkness fell on January 12, 1918, Private Hugh Barr, Company G, 26th Infantry Regiment, along with 1,800 other soldiers, walked up the gangplank on to the troop ship, ‘Mount Vernon.’ That evening, the ship sailed out from Hoboken, New Jersey, bound for France. He was unaware, as he watched the light from Lady Liberty’s torch slowly disappear, that he would never return to the shores of America.

By the time Hugh arrived in Europe, the Germans had the upper hand in the war. The Russian Empire had collapsed and the new man in charge, Lenin, had no interest in carrying on the fight. He had a communist revolution to sort out. He signed a treaty with Germany. As the Russians walked off the battlefield, Germany’s General Eric Ludendorff moved a million soldiers over to the Western Front.

The Germans, on March 21, 1918, burst through the British and French lines like raging waters fed by melting snows in Springtime. Paris was again vulnerable for the first time since September 1914 when the war had been in its infancy. General Foch, the overall leader of the allied forces, urged the American commander, General ‘Black Jack’ Pershing, to commit his soldiers to help halt the German advance. Pershing responded: “All that we have is yours. Use them as you wish, more will come, in numbers equal to requirements.” Although American soldiers were pouring into France, remarkably only one division, appropriately called the 1st Division, was, at that stage, sufficiently trained to fight. And in that division was the 26th Infantry Regiment, one of whose battle-ready soldiers was Private Hugh Barr.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe 1st Division was assigned the task of capturing the small French village of Cantigny. Although a minor encounter among the momentous engagements of World War One, the Battle of Cantigny would be the first time that American soldiers ever fought on European soil.

At daylight on May 28, 1918, with their artillery pounding the enemy trenches around Cantigny, the Americans attacked. Within a few hours they had captured the ruined village. The Germans retreated to the woods further back, from where, over the coming days, they launched nerve-racking bombardments and seven counter attacks.

As the sun came up on a beautiful summer’s day on Friday, June 7, 1918, the deafening roar of German shells shattered the stillness. Hugh, crouched in a trench, slumped over, blood oozing from his tunic, as hot metal shrapnel tore into his side. He was rushed by ambulance to a field hospital located in a chateau in the village of Bonvillers, ten miles from the front. That night, a priest anointed Hugh’s forehead and absolved him of his sins.

By morning, Private Hugh Barr had left the sorrows of this world behind. Dressed in his uniform, he was placed in a pine coffin and, with full military honours, buried in the cemetery beside the church in Bonvillers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen the war ended, the American Government contacted the next of kin of fallen soldiers with an offer to bring their loved ones home. Catherine Barr accepted that offer.

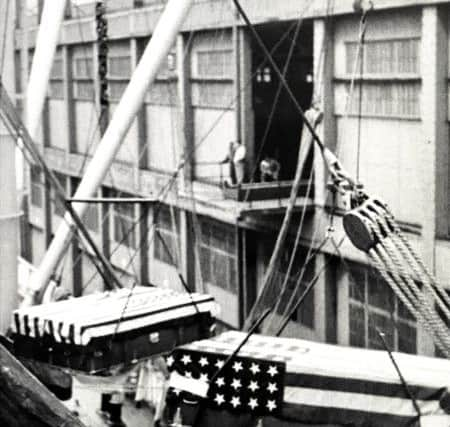

Shovels sliced through the soil on a damp January day in 1921 and slowly removed the earth from the decaying coffin of Hugh Barr. His exhumed remains were gently placed in a lead lined casket and taken from Bonvillers to the port city of Antwerp. There, over the coming months, he rested in a vast warehouse along with the sons of other mothers waiting to go home.

A small article appeared in the ‘Derry Journal’ newspaper on Friday, November 4, 1921. It stated: ‘The Head Line steamer, Orlock Head, arrived from Antwerp at Dublin yesterday flying her flag half-mast. She carried 23 caskets containing the remains of Irish-American soldiers who fell in the Great War. Amongst these were Hugh Barr, consigned to Mrs. Catherine Barr, Co. Donegal.”

On Wednesday afternoon, November 9, 1921, a hearse made its way up the Main Street in Moville and turned left onto the Malin Road. Harry Barr, sitting cross-legged on the floor, looked up from the coat that he was sewing, got to his feet and walked out to the street. With the help of three other tailors from his workshop, he carried the American flag-draped coffin, containing his brother’s remains, through the front door.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA pale sun broke through a cold and grey dawn on Friday, November 11, 1921. In Ballybrack Cemetery, three years to the day since the guns had fallen silent on the Western Front, the church bells chimed the eleventh hour.

Catherine Barr, worn down by grief, watched as her son was lowered into his grave and enveloped in the warm embrace of the sodden brown clay.

Willie lay among the missing in Flanders fields. Hugh had returned home to her.