Bloody Sunday 50: ‘People were stunned into silence. The post-traumatic stress has passed down’

and live on Freeview channel 276

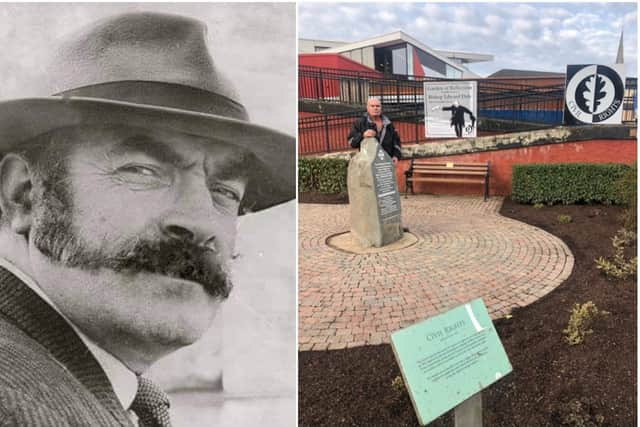

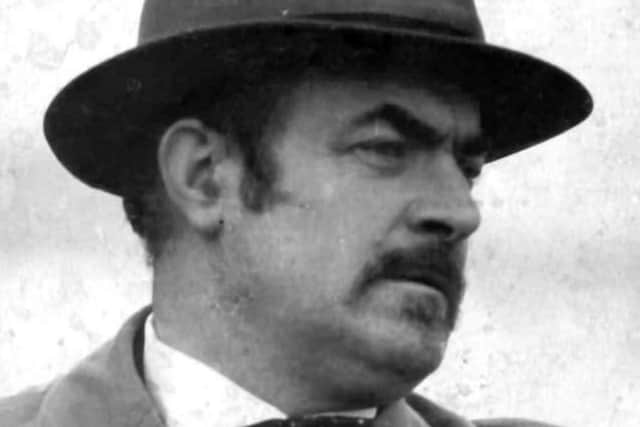

Vinny Coyle was known across Derry as distinguished chief steward on the anti-internment march that set off from Creggan on January 30, 1972 as well as many others. He was an iconic figure of the Civil Rights movement, a gentleman known and liked by all.

Vincent was also there stewarding that day along with his father, and the horrors visited upon the people of Derry, he said, left a trauma that is still felt generations later.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSpeaking about the context in the lead up to the January 1972 march, he recalls: “Since around 1964 it was about housing conditions, welfare conditions, unemployment conditions, it was about the mainstream politick in the city, gerrymandering. Gerrymandering in the council had to be done, we had to get rid of the Derry Corporation, the housing Trust which became the Housing Executive.

“I think it was the Today programme filmed Duke Street and it opened the eyes of people. I was horrified. Something strange happened to me that day to see the police, the violence, the anger on their faces. There was a couple of hundreds of us but there was 6,500 in the Brandywell at a football match and it was those people who were infuriated when they heard about the water cannons, police. When we got home to Rossville Street the city erupted.”

The week before Bloody Sunday another anti-internment march was met with CS gas and rubber bullets on the beach at Magilligan, north of Derry. “When we got there we found it was barricaded off, barbed wire and the army supported and backed up by the Parachute Regiment. Why we had gone to the beach was to show those young men in those camps and civil rights activists that we were with them and that we understood that they were being unfairly held. There was no justice. In those days we had the Special Powers Act - if you were caught with a Tricolour you could be jailed for seven years. There were so many laws against nationalists in the six county statelet and somebody had to stand up and break the mould.”

Mr Coyle said the civil rights movement involved people of different backgrounds and women were very much to the fore. “Ivan Cooper, dear family friend, he was from the Protestant community. Ivan worked in shirt factories, and the women there were the backbone of the city, and then we had the dockers and my father and all the Coyle family were dockers. He was the chief steward of civil rights and he was able to draw on the dockers, working men and they would put the badge on and go out, keep the peace. Derry women are the true silent strength of this city. Derry mothers are the most incredible human beings on this planet. And it’s because they never looked for anything. It was like Bishop Daly, the work he did on the ground, he never looked for anything, he was just Bishop Daly, and after he retired he worked in the hospice.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“He was there on the day and he took care of the wounded and dying. I’ll never ever forget those photographs of Jackie Duddy, [Bishop, then Father Daly] giving the last rights and the way he went down Chamberlain with the white hankie, the blood on it, in front of the paratroopers and he did put his life in his own hands and he was protecting the people who were carrying Jackie Duddy. The individual bravery shown that day by people, even by the Knights of Malta, some were even shot crawling to the wounded.

CIVIL RIGHTS

“We had based a huge part of the Civil Rights programme on Dr Martin Luther King, and Mahatma Gandhi because we had realised the British are really good at war but absolutely hopeless at peace, they can’t deal with peaceful protests.”

In fact, he adds, the distinctive black and white Civil Rights emblem here with its oakleaf motif was a nod to the struggle of oppressed black communities in the US. “We identified with that. Derry especially was a second class city, and Strabane, and to this day.... Protest songs were very important. After the Battle of the Bogside Luke Kelly and The Dubliners came for a fleadh, and ‘We Shall Overcome’ became the national anthem for people who were downbeat on both sides off the Atlantic and around the world... we saw the riots in France, in Prague, the world was opening up, it was an enlightening time and a lot of that was down to the world media opening up.”

Like his late father, Vincent would go on to forge life-long friendships with some of the people who were pivotal on Bloody Sunday and to the non-violent Civil Rights movement like Ivan Cooper, John Hume and Bishop Edward Daly, all of whom have sadly passed away over recent years. Mr Coyle, with the backing of local people and others created the Garden of Reflection in Bishop Daly’s memory in the heart of the Bogside. This weekend the bench there at the entrance to Glenfada Park will be draped in a black flag, an image of Bishop Daly will be erected and black flags will be erected.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis is to show that the march on January 30th 1972, Mr Coyle stresses, was a peaceful demonstration, a cry for a political solution ‘because the Troubles were waning’.

“Internment was in the way of that,” he said, adding: “When we left the Creggan it was an anti-internment, civil rights, peaceful demonstration. At 4.30pm that day the British government made it Bloody Sunday. It was as if they were there to exact some kind of price from people who had come out peacefully. It was also a last ditch attempt by the Civil Rights movement to have internment abolished. 90% of the internees would have been nationalists and a huge percentage of them were civil rights activists.

“Bloody Sunday came from a long line of protests, anti-internment protests. It was people looking for justice, and truth with justice, and what they had seen was the colleagues they had gone on marches with that had demonstrated non violently were the ones being arrested, hooded men, men beaten, tortured to get them to admit to something they didn’t do, because they’d no evidence but they needed somebody to sign something so their signature would have made internment OK, but there was nothing there.

“I remember my father and me going to the march. We took the banner for the march. Michael McDaid who was shot that day had called to the house. He had just got a new car, he was showing it off. Him and my father always had great banter, a lovely young man.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When we got to the Creggan the crowds had gathered because people were outraged at what had happened at Magilligan. There was some horrific television footage showing the way John Hume was treated. He was our representative, he was our MP, he was speaking on our behalf, he was speaking nonviolence he was speaking the truth, truth and justice. It was about divide, conquer, intern. Internment was a terrible crime because it took everything we believed in like ‘I’ll have my day in court and I’ll prove myself’ - we weren’t given a day in court. It was very much a two tier system. Then when people did go to truth and proved their truth and reality before a jury they got rid of jury courts as well.”

Vincent said what unfolded next had an impact on the people of Derry still felt to this day.

He said the trauma was widespread given what people had endured from the horrific deaths and life changing wounds, and beyond that also the men and women who ‘had their hands behind their heads, military prisoner style’, who were beaten and arrested.

“The other thing was the poisonous CS gas chemical warfare pumped in that day that we never really hear that much about, and the amount of people with asthma, bad chests. The big thing was the post-traumatic stress that hit that particular generation and which has to this very day passed down.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDerry was forever changed by what people experienced and witnessed that day. “The city changed completely, it was our 9/11 moment. People realised how violent this British army could be. People were stunned into silence. When I talk about post traumatic stress, people were numb, they couldn’t talk. The day after Bloody Sunday there would have been hundreds of people walking around zombie like wondering, ‘how did this happen?’ Would they have done this in Leeds or Halifax or Manchester?”

Mr Coyle said that after Bloody Sunday, and particularly after Widgery, ‘an awful lot of young men and women thought the only way to fight violence is with violence’.

“No side was going to come out on top, there was always going to have to be a political settlement and I believe John Hume knew that.

“It is just so sad, he said that thousands more had to lose their lives ‘before the government would sit down and have a political solution which we sort of have now’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said that the trauma visited on people over the decades here went beyond those directly impacted by the thousands of deaths.

“It’s the people who died prematurely, it’s the mothers who lay awake at night till 4 and 5 in the morning to see if their children were in alright, fathers, people who turned to alcohol and drugs, people who took their own lives because they could not cope and had no help with PTS.”

Internment would continue for years beyond Bloody Sunday and Mr Coyle said John Hume, Bishop Daly, Ivan Cooper all knew that a political settlement would only stand a chance if it ended. “The British government made the biggest mistake of all time by looking down on the Irish and saying internment will work.”

Mr Coyle paid tribute to the dignity and determination of the Bloody Sunday families and wounded and spoke of the way in which the campaign has over the years taken on a global significance. “I don’t believe there is a country in the world who has not sent representation to support the families who took such a gallant stand against the murder carried out on the city and people who were wounded. The marching went on, the campaigning went on. What a lot of people may forget is the lonely nights those families spent because they had lost loved ones. They were the ones who could not attend christenings, weddings, they were the ones who will not see the grandchildren of the young people. The families had to carry the weight of that and still try to clear their names and get justice, and the Derry families took that stand under a huge amount of pressure. Those people who supported them during that long walk, and that long walk is still ongoing, need to be saluted as well as the people of Derry who came out in rain, hail and snow who came out to stand with these families because of the terrible injustice of Bloody Sunday and those who were badly wounded on the day.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMr Coyle also said the Derry Journal became an important part of the truth being represented. “The Derry Journal especially was the flag bearer for this city because the amount of Derry Journal staff who were on the march saw it at first hand and they had a platform and the Derry Journal became the voice of truth they put it in writing. They put it down, they had their name behind it and they had no fear or filter, and it also showed other media outlets around the world, well here’s a paper from Derry we have to quote them, and the quotes from Derry Journal were seen in papers around the world.”

Mr Coyle said the legacy of those Civil Rights giants who supported the families and who now passed on will never be forgotten. “It was something very dear to Ivan Cooper’s heart, John Hume’s Heart and to all those people who campaigned behind the families. Ivan said to me shortly after 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights movement , ‘I don’t know if I’m going to make it to the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday but would you make sure the Civil Rights are represented and we are there to support the families’.

Mr Coyle said he hopes the Garden of Reflection, which is open to all, underneath the Bogside Artists’ iconic Civil Rights mural in the Bogside will be a place for reflection and sanctuary for people today and generations to come.