The risks of a '˜No Deal' have now clearly risen to perhaps 40% to 50%

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

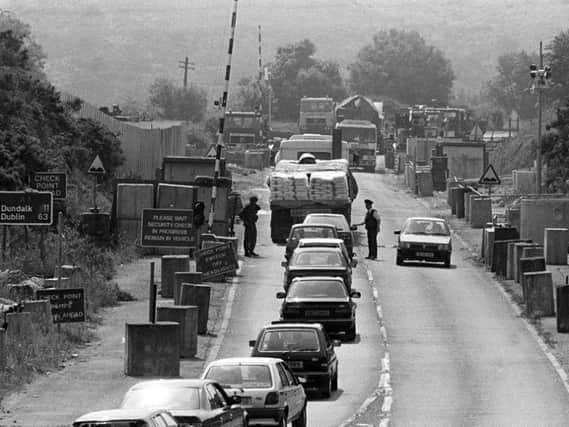

It is worth reflecting on what we mean by a ‘hard Brexit’. There is, of course, no dictionary definition. My interpretation is that it means, firstly hard borders, including in Ireland.

Secondly, leaving the Single Market and Customs Union without an agreed new trading relationship – and so the EU external tariff regime would apply.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThirdly, it means the UK not paying the previously agreed £35bn to £39bn settlement figure to the EU, which in turn would turn relationships between the UK and the EU toxic. Our friends of 45 years would become perhaps not enemies, but mutually distrusting allies.

In the latest Holywell Trust podcast, I discuss the current situation with two of Northern Ireland’s most insightful Brexit observers. Jane Morrice is the former head of the European Commission office in Northern Ireland and is currently a member of the European Economic and Social Committee and its former vice president. (The EESC is an EU body that is the voice of organised civil society.) I also speak with Seamus Leheny, the policy manager of the Freight Transport Association in Northern Ireland, whose members are some of the most affected by what happens to the Irish border and future customs arrangements.

Tellingly, neither Seamus nor Jane subscribes to the view that two sides are merely bluffing and talking up difficulties. Both accept there is a very real risk of a ‘hard Brexit’. I previously warned that the risk of a no deal outcome to the Brexit negotiations was perhaps 30% to 40%. That has now clearly risen, to a perhaps 40% to 50% risk. That is reflected in the warnings from both the UK government and the European Commission for businesses and other organisations to prepare for a possible no deal outcome. Another strong possibility, and a more welcome one, is that the Brexit date might be delayed to enable negotiations to continue for longer – this is an option the Irish government supports.

Underlying the tensions between the UK and the European Commission – backed by the remaining EU27 member states – are tensions within the Conservative Party. There is still no agreed position within the Conservative Party about its objectives in terms of Brexit. This was illustrated in the response to the government’s Brexit white paper. Strangely the foreword in that white paper from prime minister Theresa May contained the completely inappropriate line, “the country is coming together”. Its publication was followed almost immediately by the resignations of two of the most senior members of the Cabinet, a senior Brexit minister outside the Cabinet, two vice chairs of the Conservative Party and a series of junior ministers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo emphasise further the policy chaos, a series of votes then went through the House of Commons – put forward by Brexit advocates – that in effect negated the softer elements of the white paper. And it is almost inconceivable that even the previous version of the white paper would have been acceptable to the European Commission. It is essential for the Commission to provide a message to Italy, Austria, Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, in particular, that exiting the EU would leave them worse off, not better. That limits the Commission’s bargaining space with the UK.

The division within the Conservative Party is also felt across the House of Commons. Most MPs would prefer that the UK stayed within the European Union, but because of party discipline, and for many the Brexit majorities in their constituencies, they feel obliged to support Brexit. Most MPs would prefer the softest possible Brexit.

What that means in practice, though, is the absence of any clear policy. The risk is that most options to be voted on in the House of Commons might be rejected. There could be a vote against a no deal Brexit. But there might also be votes against any particular form of Brexit. Meanwhile, the House of Lords is strongly opposed to Brexit in any incarnation. This represents policy chaos, led by a prime minister who barely has the support of her party or of Parliament.

Theresa May began her tour of the UK in Northern Ireland, promoting her version of Brexit. It was not a complete disaster, but it shows no signs of winning people over here. According to the latest opinion polling, in Northern Ireland the proportion of voters who oppose leaving the EU has risen from 56% to 69%. There is also now a clear majority across the UK against leaving the EU. But that does not mean there will be a second referendum.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe sensible advice, especially for those living near the border, is to prepare for a ‘hard Brexit’, while hoping it doesn’t happen.

*The latest Holywell Trust Brexit podcast is now available at www.soundcloud.com/holywelltrust/holywell-podcast-brexit-focus-ep-8/s-wHXKs