US author Harry Wenzel provides an update on his historical novel about the wreck of the Derry-linked '˜Faithful Steward' in 1785

“The day was extremely fine; the wind favorable and all on board appeared to be happy. Each one, no doubt, anticipated a quick and delightful voyage.

“As for myself, I suffered a commixture of uncommon feelings. I stood on the deck to view the fading shore. I was leaving my homeland, forever.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“My parents, my brother, and my sisters were in my company. I, therefore, could not have mourned the absence of any kindred. I was a youth of 22; just emerging into complete manhood and active adult life. I was therefore a suitable person to seek the wilds of America. The picture was, indeed, fair.

“I saw in my imagination beyond the bright expanse of water which lay before us, a country where heroes lived; where genius expanded to full perfection; where every good was possessed. I saw, or thought I saw, another paradise, a new and flowery land, such as mortals can never see, such as mortals can never enjoy.”

James McEntire Jr.

From the deck of ‘Faithful Steward’, July 9, 1785.

These words are not contrived by the author of an upcoming historical novel of the passengers of the ‘Faithful Steward.’

These words are true, dictated and written on paper, every one of them. The McEntire family resided at Ardstraw Bridge, Strabane, County Tyrone. Some of his family farmed, James Jr. stated he was a weaver of linen.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe McEntire family consisted of James Sr., his wife Rebecca, their son James Jr., his sister Rebecca, a brother of James Jr. and eight sisters plus a sister-in-law and a nephew. James Jr. along with his sister and father, survived the wreck. The remainder, the entirety of his family perished.

One cannot conceive the mental and emotional anguish suffered by the three survivors; however, James Jr. illustrates in his own words, what it was like. In the year 1831, 46 years following the disaster, James Jr., now 68 and in ill health, dictates a complete account of his memory of the shipwreck to a Reverend McMichael, both living in western Pennsylvania.

In the account James Jr. describes he marched the shoreline searching for family and he found his young nephew, drowned – laying on the beach. He picked him up tenderly, carried him far from the ocean and buried his nephew in the sand.

He records no mention of finding any remaining relatives and he does not record the forenames of his family who perished. Such is the case with many of the survivors. No one has found a complete list of those who suffered and perished.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThrough my research I have found descendants of passengers who perished in the shipwreck, and through their efforts I am adding to the list of survivors who were published in the ‘Pennsylvania Packet,’ in 1786 following the wreck.

My purpose and goal for the current news article is to set the stage for the readership, residents in Ireland, and educate and inform them of my findings of research and writing to date. Four years prior to the wreck of ‘Faithful Steward,’ the American Revolution ended.

As I discovered in my research, a historian of colonial American history suggested, “People do not understand the depth of the role of the colony of Pennsylvania in the Revolutionary War. The magnitude of the participation by Pennsylvania residents, many who were Scots-Irish and Irish emigrants, has been grossly understated by historians.”

For me, the writer, there is a key phrase in James Jr.’s statement, at the time atop the main deck of ‘Faithful Steward.’

“I saw in my imagination – a country where heroes lived.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis reference, knowing or unknowingly, was attributed to the many people of Ireland who, having emigrated years prior, were now known and heard from in the colonies, and the Irish had knowledge of the revolutionary war via merchant ships carrying newspapers from the colonies.

James Jr. was correct in his statement – and many of them emigrated one, two, or perhaps three decades before the start of the revolution.

An important part of my focus through this historical novel is to present to the Irish reader and, of course, anyone else, a new perspective based on researched facts, and weave these facts into a story whereby they feel they have stepped back in time and are living history as it unfolds. Similarly, we Pennsylvanians must recognise a significant part of our history has to be reframed.

It is a story of people, emigrants of ‘Faithful Steward’, their friends and family, those that came before them and the intertwining connections many of them had with their brethren, merchants in Philadelphia and beyond. These people, Irish people, became the backbone of merchant business in Philadelphia and a major influence in the outcome of the war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBenjamin Franklin once estimated the population of Pennsylvania to be near 350,000 at the time of the revolution and he conjectured 1/3 of them were Irish.

Examples of Scots-Irish and Irish names

Richard and William Caldwell – Derry flaxseed merchants. It is likely Matthew Caldwell, a survivor of the ‘Faithful Steward’ was a relative.

Samuel Carsan – from Strabane. Set up shop in Philadelphia as a flaxseed and passenger merchant.

Carsan, Barclay, & Mitchell – Samuel Carsan partnered with William Mitchell and his nephew Thomas Barclay of Strabane as Philadelphia merchants. James, the father of William was a mariner and maintained an ownership interest in 20 or more sailships.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn Mease and related family of merchants included a Presbyterian minister. John brought three nephews to Philadelphia, James, John, and Matthew Mease, who carried on the business after the passing of their uncle.

Coyngnham & Nesbitt – Redmond Conyngham, from Letterkenny and John Maxwell Nesbitt of Loughbrickland.

John Maxwell Nesbitt was an influential and wealthy merchant importing goods and passengers from Ireland. Nesbitt was a founding father of ‘The Friendly Sons of St. Patrick,’ a volunteer soldier, and a moving force behind establishing the Bank of Pennsylvania, a mission designed to aid in financing the war.

Gustavus Conyngham, nephew of Redmond Conyngham, emigrated from Ireland and became a valued friend of Benjamin Franklin, even nicknaming him “The Philosopher.” Years later Dr. Franklin established the American Philosophical Society and today all of their records are housed in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Gustavus found books not to his liking but he took to the sea life. Franklin provided him a letter of Marque to be a privateer and Gustavus, together with John Paul Jones, a Scotsman, wreaked havoc on the Royal Navy. In one period of less than two years, Gustavus and other ships under his command, sunk 30 British ships and captured 27 more.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStephen Moylan – from Ireland, becomes a general under George Washington and Washington describes Moylan as having a brilliant tactical mind.

John Dunlap, born in 1747 at Meetinghouse Street in Strabane, left his home at 10 years to fulfill an apprenticeship with his uncle in Philadelphia.

His uncle goes into the ministry and John becomes a printer and founder of the ‘Pennsylvania Gazette.’ Years later he is called upon to print the first 200 copies of the ‘Declaration of Independence,’ but before he was asked to perform this task, he volunteered for the Continental Army and formed and led the 1st Philadelphia City Foot Troop.

There are many more names of individuals and people who are stories within the story itself. There is a chapter toward the end of the novel entitled, “The Society of the Friendly Sons of Saint Patrick and the Bank of Pennsylvania.” King William the III believed the colonists would fail due to a lack of a monetary base and an inability to fund war against their mother country.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe French, while lending naval and economic assistance, didn’t think the colonists could prevail. On a Sunday evening in Philadelphia merchants and citizens received word from a rider from Trenton that the British Army attacked and fired upon colonists at Lexington, Massachusetts.

The members of The Society of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick and other citizens promptly raised £315,000 to assist and finance the war. The full name of the organisation was and still is today, The Society of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick for the Relief of Irish Emigrants.

The following is an excerpt, the last paragraph from the chapter: “The Society of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick and the Bank of Pennsylvania.”

“The element of personal sacrifice became evident during the days of the revolution. Personal wealth was donated, and ingenuity, foresight, risk, and patriotism were exemplified when they created the Bank of Pennsylvania.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There were no Tories – British sympathizers, to be found among the members of The Society of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick for the Relief of Irish Emigrants. Each one, in order, took a stand – and stand they did – donating money, risking life, forming troops, volunteering for the Continental Army and the Pennsylvania Navy, diverting from merchant business to performing daily drills as soldiers, preparing for the inevitable, even dying for the cause, casting their lot with the fate of the colonies.”

Passengers who perished

Hugh and Mary Espey and five daughters (Londonderry Journal 2/11/1786) – believed to be relatives of the James Lee contingent from Donegal.

Edward Cooke and family of eight – Edward Cooke was a relative to two brothers who served in General Washington’s army.

James and Simon Elliott – brothers – swam to shore to safety, however, their father, “Wealthy Elliott” possible forename of John, plus 5 sisters to James and Simon perished.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is believed their brother William, not recorded as a survivor, also made the swim to safety. Another brother, John Elliott, came to Pennsylvania in 1784 on the ship, ‘Lazy Mary,’ a year prior and sent his father word the rest of the family should emigrate also.

Doctor Campbell – another who perished, not on a list, and nothing else is known to date.

The author has, during research, initiated contact with or has been contacted by a number of people, citizens of the United States, who have performed ancestral research of their family, tracing relatives back to someone who sailed on ‘Faithful Steward.’

And they have a desire to trace beyond them back to Ireland. Another individual, a resident of western Canada, has a keen interest in the novel as he has traced his ancestral heritage to Hugh Colhoun, linking him to two brothers, Gustavus and Thomas Colhoun, who survived the shipwreck.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

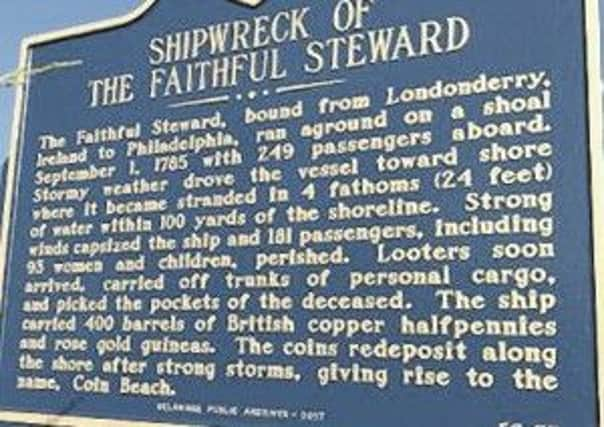

Hide AdI am still researching a potential link between the Colhouns, Hugh and Gustavus who went on to become successful Philadelphia merchants and Thomas, a mariner, and the 400 barrels of copper coinage that spilt into the Atlantic off the coast of Delaware, now Coin Beach.

And to that end – the novel isn’t complete, but will be in the near future as the final strands of research unfold, hopefully, at the American Philosophical Society and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Summation

The focus of the novel is not about the Revolutionary War, but to that end, ancestors, relatives, acquaintances of people from Ireland, were known to the passengers of ‘Faithful Steward’.

The 249 passengers were on a voyage lasting 53 days and what better way to fill idle time than to talk about those who emigrated prior to the revolution, while sitting around the long tables on the emigrant deck of ‘Faithful Steward’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere is plenty of content in the novel of the lives of the people living in Ireland, including life in the counties of what is now Northern Ireland many years prior to 1785.

The novel concludes with a description and account of the inevitable, a horrific scene, a shipwreck, and this will tell a story of its own.

There needs to be a tie-in, a connection, as the passengers of ‘Faithful Steward’ were coming to a land whereby they hoped for new opportunity, freedom not known at that time. What is clear to me, the author – this is the first time in history since the beginning of time that a new threshold, a doorway into the future opened where men and women would one day possess the means to formulate their own government, no longer forced to live under a kingship, and the Irish, now colonists, played a monumental role in forming Pennsylvania and American history.