Sean Connor's Technical Area: Are footballing talents born to succeed?

Somewhere in his hometown, a worn-out brick wall stands testament to the innate footballing mind, the maturity and drive present in the young boy, Bergkamp.

He spent countless hours practising at the wall, experimenting with the different ways he needed to control the ball, to master it. Seeing how the ball was affected by whatever part of his foot, or body he decided to control it with.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThings that still don’t occur to most professional footballers, or aspiring young superstars as they go about the development, fine-tuning and mastery of their skills. This is the work we don’t see, that lead many of us to say he or she is a natural. Well, are they naturals? Is their genius just pre-determined by biology? Or is it hard work, personal motivation, guidance, encouragement and the environment the player/athlete finds themselves within?

This type of debate has been around as long as I can remember, the nature versus nurture question. Only this week I read about the young Cora Chambers, a student at Lisneal College on the Waterside, who has just been called into the Northern Ireland Ladies Senior International squad, as they prepare for this summer’s European Championships.

The article I read called her a ‘natural talent’. I know Cora’s Head Master, Michael Allen, and I’m sure he knows there is more to Cora than natural talent. Michael promotes a work ethic, personal motivation and creates an environment for all his pupils to be the best version of themselves. At home, I am confident there is family support and of course the love that allows Cora to follow her dreams without the fear of failure.

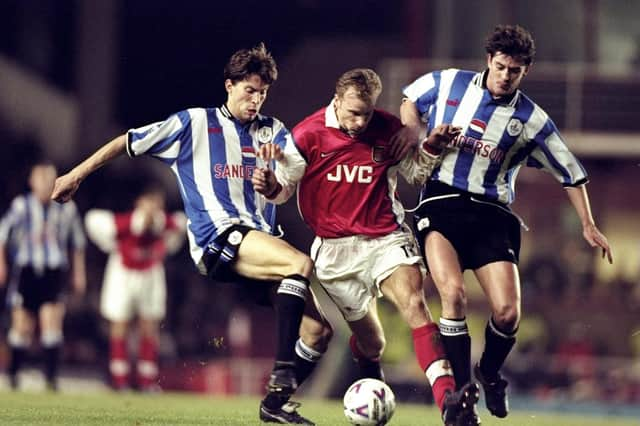

So, I decide to put my academic coaching head on and look at this question, are players like Dennis Bergkamp or Cora, just natural freaks of nature or is there more than this to the skill-set they have? Are their abilities innate or developed?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA number of theories have been put forward to explain how players learn movement skills. The majority of ball skills associated with soccer are movement skills, at their core. At the very top level these skills are used with imagination and artistry, as can be seen with Dennis Bergkamp and a host of the top players in the world today and days past. In my view, these skills must be learned, they are not innate skills within the player. The debate between ‘nature or nurture’ has long been argued, but there is enough academic literature, check out Erickson, and

Baker to name a few, who support the fact that elite performance and excellence must be learned and developed rather than simply a born gift.

Prior to the 1960s however the likes of McCoy and Young (1954) did push the role of ‘natural ability’. The most prevalent theory in regard to movement skill development has emerged from the field of cognitive psychology. The core of the theory is that, with practice, learners develop a generalised motor programme for each individual skill. For each individual skill connections are made by various spinal and supra spinal feedback loops involving muscle spindles, cerebellum and the motor cortex, as set out in ‘The Talent Code’, by Matthew Syed.

During early learning, the assumption is that movement is regulated via conscious feedback loops, involving the visual and auditory senses. As learning progresses, players develop enhanced and more refined motor programmes. They now develop sub-conscious feedback mechanisms to both refine and adapt the particular skill.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTherefore, with the correct time and environment, in terms of motivation and coaching support, and a high level of personal engagement and commitment from the athlete, any skill can be learned and developed to a high degree. “It takes 10 years of extensive training to excel in anything,” claims Nobel Laureate, Herbert Simon.

There are three stages in skill development, the initial stage involves cognitive learning, and demands practice and attention. Errors will occur as the players adapt to the skill. Performance variability is high, and mistakes are common.

The next stage or associative stage is when the player has now mastered the skill as a basic skill. Attention now focuses on refinement, adaptation and mastery of the skill within a game context. Performance consistency now increases as well as the speed at which the skill can be applied.

The final point in skill development is the autonomous stage. The skill can now be applied with limited conscious attention. Errors are negligible and infrequent; the players’ focus is now strategic and on the tactical application of the skill. The player is now advanced, or to the untrained eye, a ‘natural’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith the likes of Bergkamp, I am sure you will have your own personal favourite, it is clear to me that all of the greats, worked extremely hard at developing their unique skill set. It was through hours and years of rigorous practice, individual and collective. They all had support, much of it unseen, and defiantly they all had a passion within them to be the very best they could.

As highlighted above, the acquisition of skills is a complex and time-consuming process. Patience is required by both coach and the players. More important is the environment created and the language used by the coach, family, friends and teammates.

If this is an intrinsic motivational climate with positive language, then the players will feel relaxed and confident to make mistakes, to work on, and in time, improve their skill levels.

It is far too simplistic and lazy to say that some players are more technically gifted than others.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere is no denying the fact that some players will work on their skills and game in their own time, (these are the players that will rise to the top), but there is no excuse for not looking to improve all players to be more comfortable on the ball and to possess a greater array of skill acquisition.

As Dennis Bergkamp stated: “Behind every kick of the ball, there has to be a thought.”

So, the next time you hear or even are about to say, this player is a ‘natural’, maybe you should stop and think about all the hours of practice, the process of skill development and adaptation. The words of advice, support, and of course the love and encouragement that, the player has received.

Maybe, it’s not such a simplistic thing as natural talent after all?