Bishop Maginn: (Part 2): A Forgotten Hero from the time of Ireland's An Gorta Mór

and live on Freeview channel 276

In the spring of 1847, the British government established soup kitchens, offering temporary relief from starvation. However, a few months later, in August, the responsibility for all relief efforts was transferred to the Poor Law, resulting in the closure of these soup kitchens.

Realising that assistance from the British government would be insufficient, Bishop Maginn tirelessly sought aid from various sources, achieving moderate success. By the summer, he expressed gratitude for the generous donations received from organizations in Canada, France, Italy, England, and the United States. Notably, Archbishop John Hughes of New York, who, like Maginn, hailed from Ulster and who played a significant role in the development of the Catholic Church in the United States, was among the contributors.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

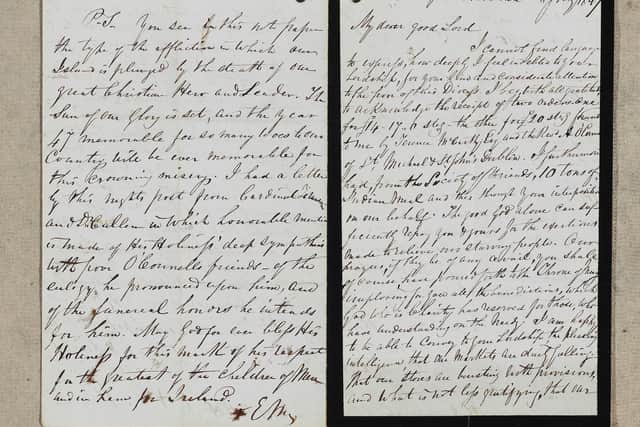

Hide AdA letter of thanks from Maginn to Hughes, discovered by this author in the Archives of the Archdiocese of New York, was edged in black, a customary practice symbolizing sympathy for the deceased—in this case, for Daniel O’Connell. It was dated 2 July 1847. Here is an excerpt:

‘My Dear Good Lord,

I cannot find language to express how deeply I feel indebted to your Lordship, for your kind and considerate attention to the poor of this Diocese.

… America has nobly done its duty and our gratitude to it will be as enduring as the foundations upon which our Island rests. Ireland will be henceforth to her (if not her ally) at least her friend with a friendship ever green as her own native shamrock and whether in war or peace the full spread of the Eagle’s honor or disgrace we shall consider our own …’

Your obliged and devoted Servant in J.C. Edward Maginn.

Similar to Hughes in New York, Maginn held the British government responsible for the death toll in Ireland. Assisted by his fellow Roman Catholic priests in Derry, Maginn compiled a list of all those who had succumbed to starvation in the city between November 1846 and April 1847. His outspokenness was commended in the Catholic newspaper, The Vindicator, which believed that his actions instilled hope in the entire country:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad‘Honour to the Catholic Bishop and clergy of Derry. The Right Rev. Mr. Maginn and his clergy voice the sentiments that indignant Irishmen should feel and express at this significant crisis. There is still a soul in Ireland ...’

One of Maginn's responses to the dire situation in the city of Derry was the establishment of a convent for the Sisters of Charity, motivated by his compassion for the suffering population. Recognising that long-term, structural changes were necessary to avert future devastating famines, Maginn wholeheartedly supported the tenant rights movement. This movement garnered support from individuals of all religious denominations, and as the bishop eloquently stated, ‘Should we not be united in all matters that promote the common good?’

Despite the dire conditions endured by the impoverished, Maginn remained steadfastly opposed to emigration as a solution, particularly when it involved the British government’s colonisation scheme to British North America, endorsed by several Irish landlords, including Lords Sligo, Lucan, and Ormonde, as well as 21 MPs. The aim of this scheme was to facilitate the emigration of up to 300,000 people, with a significant portion of the funding provided by the government.

Initially, Maginn held strong nationalist political views and denounced the Young Irelanders when they split from O'Connell in 1846. However, as the devastating events of "Black '47" unfolded, his stance changed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne of the leaders of the Young Ireland Rising in 1848 was Thomas D'Arcy McGee, who managed to evade arrest and escape to New York. In 1857, McGee relocated to Canada and dedicated himself to convincing Irish Catholics to collaborate with Protestant British church members in forming a Confederation that would unite divided British North American colonies and create a strong Canada. McGee, known for his skilful rhetoric as a writer, published numerous works, including ‘A Life of the Rt. Rev. Bishop Maginn.’

A decade before writing the biography, the 23-year-old McGee was a fugitive evading trial in Dublin when he encountered the bishop in Donegal. According to McGee's biographer David Wilson, there is no doubt that Maginn sympathised with the revolutionaries and aimed to protect them from falling into the clutches of the authorities. While he may not have personally orchestrated the arrangements for the young revolutionary's escape, as McGee himself stated, ‘some of his kind and courageous clergy were the chief promoters of it.’ Local folklore in Donegal celebrates the story of McGee being taken to Tremone Bay, near Culdaff in Inishowen, where Robert McCann rowed him to a waiting ship named the Shamrock, sailing from Derry bound for Philadelphia.

Unfortunately, Maginn's life and service as bishop were abruptly cut short in January 1849. On the eve of the third anniversary of his consecration, Maginn passed away, succumbing to typhus, then referred to as famine fever. He was laid to rest in his beloved Buncrana, in the shadow of the same St. Mary's Parish Church that he had just completed building the previous year. The Gothic Revival church dominates the landscape northeast of Buncrana and stands as a testament to his dedication during a time of limited resources.

Maginn's untimely death was not only grieved by his parishioners in Derry and his adopted home of Donegal, but also impacted the Catholic Church in Ireland, which was seeking leadership in the aftermath of the devastating Famine.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis two-part profile of Bishop Maginn by Turlough McConnell was extracted from his original contribution to the book ‘Heroes of Ireland’s Great Hunger’ edited by Christine Kinealy, Jason King, and Gerard Moran (Cork and Hamden CT: Cork University Press and Quinnipiac University Press, 2021), pages 179-189.