Derry and the 1641 rebellion

Mrs Anne Smyth, her 17-year-old daughter-in-law Susana Wright, her 18-year-old servant Anne Walton and another servant called Bridget, were all stripped and abused by rebels led by Lawrence Garnon during an armed raid of their County Derry home on October 23, 1641, the day the rebellion broke out.

In Ballykelly Peter Gates was robbed of corn and cattle and lost £400 - the equivalent of around £50k in today’s money - when rebel Irish from Dungiven came down from the hills wreaking havoc.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTen years after the rebellion a rebel called William Bowe stuck his head through the mud wall of a house on the outskirts of Derry and boasted to William Erwine how he had killed his brother Robert, “whilst a kerne on Barnesmore”. These tales are contained in the testimonies of people attacked by the rebels during the revolt. Although the historiography is divided as to how many died the death toll ran well into the thousands.

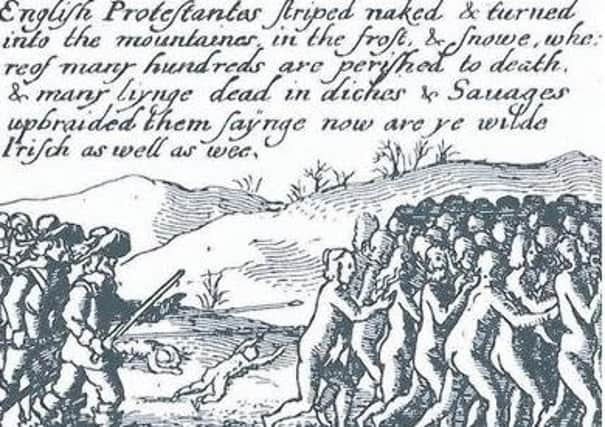

The revolt of the propertied Irish Catholic gentry against the English administration in Dublin Castle ultimately degenerated into ethnic violence between the native Irish and newly-arrived English and Scottish settlers.

This was largely centred in Ulster around the leadership of Phelim O’Neill who was concerned that Thomas Wentworth, the 1st Earl of Strafford, was planning a new plantation drive on behalf of Charles 1.

After the Nine Years War the unexpected flight of leading Irish chieftains to the continent (1607) and the revolt of Cahir O’Doherty (1608) enabled the state to confiscate vast tracts of Ulster.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut it wasn’t as successful as had been hoped and enraged many of the dispossessed Irish who had lost land and were eager for a chance for a counter-Plantation.

So when in 1641 the Irish Catholic elite - fearful of an anti-Catholic alliance of Scottish Covenanters and the English Long Parliament - decided to seize Dublin Castle and rule Ireland as loyal noblemen, supportive of Charles I but insisting on Catholic rights - the dispossessed native Irish of Ulster seized that chance.

The Irish gentry quickly lost control of the peasantry it raised. The 1641 depositions - witness testimonies mainly by Protestants - concerning their experiences of the 1641 Irish rebellion document the loss of goods, military activity, and the alleged crimes committed by the Irish insurgents, including assault, stripping, imprisonment and murder.

It is clear thousands of Protestants were massacred during the course of a few tumultuous months.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEdward and Margaret Moore also had four pounds, 17 shillings and six pence taken from them in Cavan. This was equivalent to over £600 in today’s money - whilst a small amount of flour intended for their children was also seized.

The rebels then stripped their surviving five year old child of its clothes and they were forced to travel for four days from Cavan to Drogheda without any food.

Starving and miserable they struggled along eating only “herbes gathered in the fieldes” and a twopenny loaf given to them by some troops.

The Moores eventually made it to safety and were among dozens of Protestants from County Derry who retold their experiences to the authorities in subsequent years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn April 9, 1644, Edward Moore told the authorities “they were English dwelling at Londonderry that they tooke theire way by Inniskillin hoping to meete a brother of his the deponents Edward Moore whom they found to have been killed”.

They were trying to get to Dublin from where they would travel onwards to friends in England but were brutally accosted in Cavan.

“Thereupon the said Irish laid hold on him the deponent Edward Moore stripping him out of all his clothes and shirt leaving him quite naked: and after stripped starke naked her the deponent Margaret Moore in doing whereof they said the Irish did cast off from her back a child of three quarters old and thereby broke the skull thereof the braines appearing, so as it the next day died which child and one other about five years old stripped out of their clothes by a woman that was in that company, ” their testimony reads.

The rebels even tore up a makeshift passport carried by the Moores that had been supplied by Captain Henry Vaughan of Derry and when Mr Moore asked who they were they merely told him to report “they were the Realyes who had so used them”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis was a reference to the O’Reillys of Cavan who in 1601 the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Baron Chichester, had described as the head of a “hardy and warlike people”.

“The chief of them are the O’Realyes, of which surname there are several septs, most of them cross and opposite one to another,” Baron Chichester had reported forty years before the rebellion.

The Moores weren’t the only settlers to suffer severe mistreatment during this upheaval.

Mrs Anne Smyth, Susana Wright, Anne Walton and a servant girl referred to as Bridget, were all stripped and abused in South Derry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn September 15, 1642, Mrs Smyth described their ordeal to the authorities saying 40 rebels led by ‘Cormacke o Hagan, ’ ‘Owen o Hagan, ’ and ‘William Tath’ - entered Moneymore by force of arms, seized the keys of the castle and raided it of arms and ammunition before raiding local houses for food, provisions and money.

She said her husband - described as a gentleman of the city of Dublin - was away when Lawrence Garnon and a group of rebels entered her home and proceeded to abuse and rob the inhabitants.

According to her testimony: “To coulour his rebellious and felonious intention then saying vnto this Examynat that hee had a cumission to serch the said house for said hee itt is suspected there is money and the said Garnon having stripped this examynat to the smock, tooke from her the keyes of the chests and trunckes that were in the said house which hee Ransaked and did then take and carrye awaye with him twoe silver spones, a topp of a silver salt, twoe silver Beakers, twoe silver Bowles, one smale trunck certen Lynnesn: and other things to the value of twentye poundes and vpwards part of what the former Rebellious persons had lefte behind there.”

As it happened Garnon retired to the Drapers’ castle in Moneymore which the rebels had seized but was subsequently arrested having been spotted on the Derry Walls.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was seized on suspicion of “being a rebellious spye being taken walkeing on the Cittye wales there, and enquireing of the Armes and strength of the said Cittye.”

Five or six weeks after being stripped and robbed by Garnon, Mrs Smyth interviewed him in the confines of the Derry Gaol.

She asked him “wherefore he dealt soe cruelly with her att Moneymore” but Garnon merely replied that he had been following orders.

Mrs Smyth then travelled from Derry to Dublin on a ship with a maid servant and four of her children whilst Garnon escaped.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAccording to her testimony Mrs Smyth “knoweth not what became of the said Lawrence Garnon nor how he escaped thence”.

On June 6, 1643, Peter Gates, with interests in Ballykelly, Balteagh and a place referred to as both “Dromgawny” and “Drumgawny” described how a group of ‘o Canes, ’ ‘McManus’s, ’ ‘o Mullens, ’ and ‘McGilleduffs, ’ under the leadership of ‘Manus McRichard o Cane’ came down from ‘Ballinasse’ which was described as a parish in Dungiven to “deprive, rob or otherwise despoil”.

In November 1641 the group of around 500 or 600 rebels “did alsoe perpetrate and Comitt divers other outrages and cruelties and Killd many protestants his neighbors by name one Thomas Bunting John Gardner Vaughan Morgan and divers others”.

According to Mr Gates Manus McRichard O’Cane had been trusted by Sir John Vaughan with ammunition and arms to keep the Castle of Dungiven in good order but had betrayed this trust to turn rebel and become “the most bloudie and cruell villain of all the rest”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJames Farrell was described as “a papist of Ballykelly” who after promising protection and favour to his English neighbours sold them out.

Mr Gates described how “with the assistance of divers his bloudy confederats” Farrell assaulted and set upon the English “and most barbarously slew and murthered them”.

Intriguingly the Mayor of Derry Henry Finch - long after the massacres - conducted an enquiry into a number of murders when William Erwine came forward in 1653 to give an account of an encounter with a rebel called William Bowe.

One Sunday in early April 1653 Mr Erwine said he was in a house in the suburbs of Derry with a man called John Gilpattricke. They were disturbed by a knock on the door by a drunken William Boye who was refused entry by the woman of the house.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUpon being refused entry Boye threatened to force the door open and sticking his head through a window told the occupants he would break it down. The householders yielded and let the rebel in and it was then that he stuck his head through a “wattle wale” and spotted Mr Erwine.

According to Mr Erwine’s testimony Bowe said: “I knowe you well enough to which he made answere I doe not you, what way came you to know me, to which the said Boye answered he knewe the examinant ever synce he Killed this deponent’s brother Robert Erwine; this examinant askinge him what he did with the other man names Thomas Tomson that was with him and the women and children, what should I doe with them I kild the Boddowe and the rest and put them in a hole; demandinge of him wher it was when he did this he answeered the deponant; that he was a kerne upon Barnesmore 7 years together.”

The Mayor asked Mr Erwine if Bowe was drunk. He replied that he was or pretended to be because he was so unruly. The householders tried to throw him out and Mr Erwine eventually threatened him with a knife telling Bowe he would “bleed” him until a guard came and removed him.