Messines park 80 years on: The night the Luftwaffe bombed Messines Park

The festival of Irish singing, dancing and speech was nineteen years old that April and the Guildhall was full of the sound of soloists, choirs and the tattoo of taps on wooden boards.

The war had, of course, impinged on the second city of Ulster but in the Great Hall and the Minor Hall there was hardly a thought of danger. If Belfast people had believed that the city would not be bombed, Derry people knew for certain that the oak grove of Colum Cille was invulnerable. Who would want to bomb us? Didn’t the saint promise that no disaster would ever afflict his beloved city?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMost of the children had been taken home by 10.30pm but there were still many people in the building enjoying the later competitions. The sirens sounded at 10.40pm and the platform steward announced that a raid was imminent.

No one in the audience showed any sign of alarm - they knew from experience that the sighting of German planes over the Irish Sea was responded to with a general alert but parents who still had young children with them in the auditorium hurried them home.

Charlie Gallagher was on ARP duty that night and he recalls in his book, ‘Acorns and Oak Leaves’ (1981), that, when the alert began, he went to his first aid post at the corner of Queen Street and Great James Street close to the Guildhall.

All was quiet for more than an hour until the word came through that, ‘Belfast was being hammered again.’ One of the voluntary first aid officers asked the company to join her in prayer ‘for those who may die tonight’. Not long afterwards, one of the wardens looked outside his post and discovered that flares were being dropped.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThen came two ‘deafening explosions’ and an emergency call for numbers one and two ambulances to be sent to an ‘incident’ at Messines Park.

It was a beautiful moonlit night with broken cloud, perfect for the Luftwaffe’s purpose, and Charlie Gallagher reached the corner of Buncrana Road in less than five minutes. As the ambulance turned the corner, normal sounds seemed different.

There seemed to be fog and from the strange note of the tyres he felt he was driving over earth, as though he were in a field. The fog, he realised, was dust borne on thermals and the odd sound the tyres made was due to the sand that had covered the tarmac.

An ARP warden loomed up out of the artificial haar: ‘Corner of Messines Park. Direct hit on two houses. There’s a naval rescue team; that’s their floodlights. Stand by for their instructions.’ Gallagher’s ambulance had had to stop short of Messines Park because the mine explosion had caused a deep crater now filling with water from mains and sewers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUnderground telephone cables were exposed and the expert naval rescue team, equipped with mobile floodlights, were already sifting through the rubble. In all, thirteen bodies were identified that night or the next day.

55 Messines Park had been the home of the Collins family and the mine blew down the gable wall. James Collins, who had been born in 1880 and had served in the Royal Navy in the Great War, and his twenty-one year-old daughter Ellen died when the wall fell; they were buried at Glendermott New Cemetery.

Next door, in number 57, William Alexander McFarland, a member of the Home Guard, died but his wife Elizabeth had spent the night in her parents’ house in Hawkin Street and it was there that the body was waked before burial in the City Cemetery.

The Murray family, at number 59, had consisted of parents, William (50) and Mollie (39), and children Kathleen (by a previous marriage), Ita (13), Philomena (10) and Sheila (10 months). They died together. 61 Messines Park had been the home of the Richmonds: father John (53), mother Winifred (45), their son Owen (18) and baby daughter Bridie (14 months).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

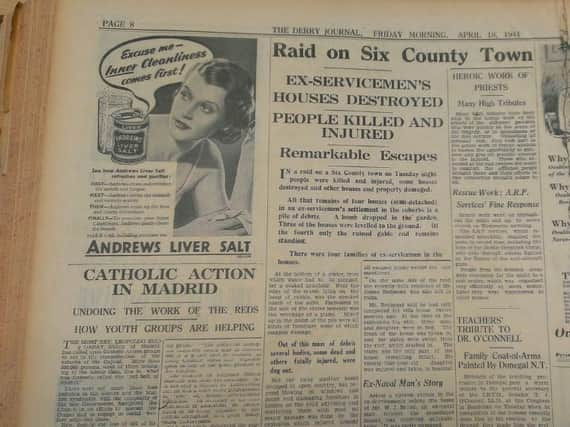

Hide AdThe ‘Journal’ did not publish the story until Friday, 18 April. The Wednesday edition had been put to bed before the raid and its headline was the unspecific: ‘Raid on Six County Town’. By the time this edition was published, the absolute shock had diminished a little, at least during the hours of daylight, and the conversation had turned to consider the stories of survival.

A boy aged twelve was blown out of bed but was uninjured in spite of flying glass and rubble blown into his house. Another boy, named as Daniel Diggin (14), though buried under a heap of plaster and rubble but protected by a heap of heavy framed pictures, was pulled out from the rubble without a scratch. Stephen Rabbitt, the owner of a small shop, had been outside when he saw the parachute bomb float gently down.

He ran into the kitchen of his house where his mother and father were sitting. They all escaped injury but his shop and house furniture were destroyed. One veteran of the Messines Park blitz was Bertie Downey who, then thirty-one years of age, had a house and shoemaking business less than fifty yards from where the one of the landmines made its stately descent.

He recorded his memories for local radio in his ninety-first year in April 2001, the 60th anniversary of the raid. His house was one of many damaged by the blast.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe found it sadly ironic that four of the dead had survived the Great War only to die in their beds less than a quarter of a century later. He recalled the trepidation he felt as he waited outside the room in the City and County Hospital where the dead were laid out.

He had been asked by the police to help identify the bodies of what had been near neighbours and he felt a mixture of dread and relief that he had survived. He was, too, one of the earliest country refugees - heading out to his brother’s house a few miles away at Galliagh.

He remembered that the Buncrana Road was crowded with people that April morning as all those who lived near where the paramines had landed sought shelter in Donegal, the border of which was less than three miles away.

Derry was not attacked again during the war. The remaining years of the war meant excitement without danger for a small city that had known little of comfort or glamour or decent employment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy 1944, the dimout had replaced the blackout and the church bells, silent for so long since they were to be the signal of a German invasion, were heard again. With the historians’ great gift of hindsight, we can understand that Derry’s avoidance of further raids was sheer good luck.