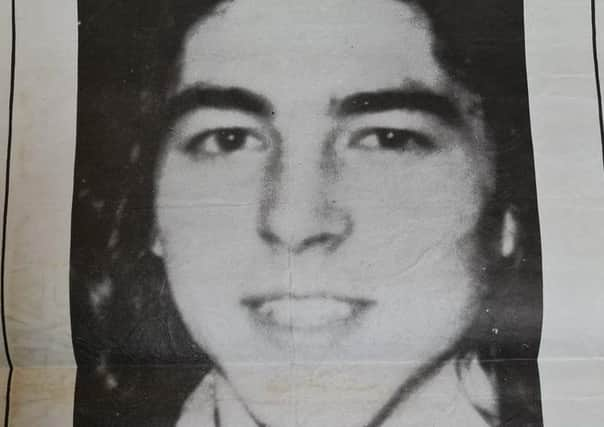

Pat Sheehan ahead of Derry hunger strike vigil - ‘They were ten of the best men we had’

The Remembering 81 Committee Vigil has been called to honour the ten young IRA and INLA prisoners who died in the seminal prison protest - Bobby Sands, Francie Hughes, Raymond McCreesh, Patsy O’Hara, Joe McDonnell, Martin Hurson, Kevin Lynch, Kieran Doherty, Thomas McElwee, and Mickey Devine.

It will be attended by representatives of the hunger strikers’ families while the main speaker will be Pat Sheehan, the West Belfast MLA, who spent 55 days on the strike after being selected to replace Kieran Doherty who had died on August 2, 1981.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAhead of his visit, in an interview with the Derry Journal, Mr. Sheehan shared his recollections of what was a pivotal moment in history

“By October 3 I was very seriously ill. I had been examined by a consultant from the City Hospital the previous Wednesday [September 30].

“He asked me to lie down on the bed and prodded his fingers up under my rib cage on the right hand side and I nearly went through the ceiling with the pain.

“He wasn’t trying to hurt me but he said, ‘Your liver has become enlarged and is starting to shut down. Even if you end your hunger strike right now I can’t guarantee that you’ll survive because there might be irreparable damage to your liver.’ Fortunately for me the hunger strike ended four days after that.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe strike had commenced 216 days earlier on March 1, 1981, when Bobby Sands refused food in protest over the refusal of the British Government to recognise the IRA and INLA inmates of the H-Blocks as political prisoners.

The roots of the strike can be traced back to the hard-line stance of the British Labour Secretary of State Merlyn Rees who on an earlier St. David’s Day, in 1976, had ended special category status in what republicans regarded as part of a new ‘criminalisation’ strategy.

There followed the ‘blanket’ and ‘no-wash protests’ and the hunger strike of late 1980 which was called off after 53 days with no loss of life, after the British appeared poised to concede the prisoners’ essential ‘five demands’ which were: the right not to wear a prison uniform; the right not to do prison work; the right of free association with other prisoners; the right to organise their own educational and recreational facilities and the right to one visit, one letter and one parcel a week.

Mr. Sheehan believes the election of Bobby Sands as MP for Fermanagh/South Tyrone in a by-election in April 1981 was the beginning of the end of ‘criminalisation’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The big thing for all of us during the hunger strike was when Bobby Sands was elected for Fermanagh/South Tyrone. At the time Thatcher had said the prisoners had no support, the IRA had no support, and then the people of Fermanagh/South Tyrone came out and elected Bobby and blew that assertion completely out of the water.

“In a sense that was really when criminalisation ended. Obviously we didn’t realise that at the time. We were stuck in a bit of a bubble. We didn’t understand the impact the hunger strike was having outside and the deaths, particularly of Bobby at the start, were having - not just in Ireland but internationally.

“When we reflect back now 40 years later that was the first tentative steps into an electoral strategy for the movement. Sinn Féin began contesting elections after that and went from strength to strength.

“If you consider that the whole rationale behind the criminalisation policy was to isolate and marginalise republicans and ultimately to defeat the IRA - the outcome was actually the opposite of that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Many young people were inspired by what happened in the H-Blocks. Many of them joined the movement through the ‘80s and then Sinn Féin began to grow electorally, to the point today where Sinn Féin is the largest party on this island.

“So the strategy of the British to defeat the IRA and defeat the republican struggle failed in 1981 and I think we are still feeling the repercussions of that even now.”

Mr. Sheehan explains how he did not know all of his fellow hunger strikers personally, including the Derry men, Patsy O’Hara and Mickey Devine.

“I knew Joe McDonnell very fleetingly. I met him in Belfast once when I was a kid. I didn’t know Patsy [O’Hara]. I didn’t know Mickey Devine, Raymond McCreesh or Martin Hurson because they were all in H5. I was in H4 and then H3 so I knew Kevin Lynch, I knew Kieran Doherty, I knew Thomas McElwee, and Bobby [Sands], of course, too.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPat believes the ten men who died between May and August of that year all would have been significant leadership figures within their respective movements had they survived.

“It wasn’t just that we lost ten men. We lost probably ten of the best men that we had. I’ve no doubt that had Bobby Sands lived he would be one of the leaders of the movement. The likes of Frank Hughes, Tom McElwee, Kieran Doherty - they were all leaders in their own right.

“It was ten of the best that we had. It was a massive loss for all of us. The question, was it worth it? I suppose the best way I can answer it is that if we were in the same situation again would I do the same thing? And I would.

“What I would say is that it was worth it for me and I would say for those who died on hunger strike - I don’t want to put words in the mouths of the dead - but they were all prepared for it and they were all willing to do it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When I was selected to replace Kieran Doherty on the hunger strike I got a comm [communication] from the leadership saying, ‘You have volunteered to go on hunger strike and you have been selected to replace Vol. Kieran Doherty. If you have any second thoughts stand aside now and nothing less will be thought of you but if you follow through in this course of action you will be dead in two months.’ It was as stark as that but even at the last moment you were being given an opportunity to stand aside and I would say all the lads who went on hunger strike got that same comm offering them a way out.”

Throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s tensions simmered between the IRA and the INLA but inter-republican sectarianism was not a factor inside the H-Blocks at that time.

“Even though Patsy and Mickey were INLA and Kevin Lynch as well, inside the H-Blocks it didn’t matter what organisation you belonged to.

“That’s not to say there wasn’t a certain amount of tension afterwards and on the outside as well but at that time on the hunger strike nobody even thought about what organisation people belonged to. We were all standing together. We had a common cause and that was that.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSixteen years ago controversy flared after the publication of ‘Blanketmen’ by Richard O’Rawe, the prisoners’ public relations officer in the H-Block during the prison protest.

Among the book’s claims is that in July 1981 a comm containing details of a deal with the British sufficient to meet the prisoners’ demands had come into the jail. This, O’Rawe contended, he discussed with the IRA O/C at the time, Brendan ‘Bik’ McFarlane, speaking in Irish, from cell to cell.

This version of events has been rejected by McFarlane. Asked for his view, Sheehan, says he does not find O’Rawe’s contention plausible.

“I wasn’t in that wing at the time when this discussion is supposed to have taken place between ‘Bik’ and Richard. If you ask me it would have been impossible to have had a conversation like that and not for everyone else or at least some others to have heard it because the currency at that time in the prison was scéal [news/information - literally story]. Who had a bit of info? Who knew a wee bit here or there?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“If the leadership were up at the window or down at the pipe having a conversation about the situation someone else would have heard it. That is my view and there is nobody, as far as I’m aware of, backing up what Richard says.”

Pat was among six remaining prisoners who came off the strike on October 3. The others were Jackie McMullan, Hugh Carville, John Pickering, Gerard Hodgins and James Devine. Several others had been taken off by their families or for medical treatment during the previous months.

“It was a pretty demoralising period after the end of the hunger strike. We got some of our demands. I suppose getting our own clothes was the main thing. We hadn’t got all the demands and the year after the hunger strike for me would have been the most demoralising period in jail. Initially we weren’t sure what we should do so we had a period of reflection and decided to push on and try and wreck the system from within. Having our own clothes and being out allowed us to do that and then that led to the big escape in 1983.

“I got out in 1987 and at that stage there was still quite a bit of tension in the prison. I ended up back in again in 1989 and back in the blocks in 1991 and the whole situation was completely transformed. The Brits had effectively thrown in the towel and conceded everything. They were negotiating with the leadership.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said, at that time, Raymond McCartney had a leadership position among the prisoners and “there would have been ongoing negotiations with him, the prison governors, the NIO, and so on”.

Pat says he is honoured to lead the tributes to his former comrades in Derry on Sunday. He remains convinced they chose the correct course in 1981.

“You have to understand the motivation. For us, it wasn’t just about prison conditions but it was about a broader strategic attempt by the Brits to use us to defeat the IRA and to defeat the struggle in general. That was a very heavy burden on our shoulders and we just weren’t prepared to bend the knee. For me what we did was the right thing to do at that time.”