The amazing story of the WWI hero buried in Derry with no headstone

David Jenkins knew he was on to something special when he first heard the story of a Captain Kokeritz who, in 1917, had been rescued off the west coast of Ireland after spending days at sea in an open boat, writes SEAN McLAUGHLIN.

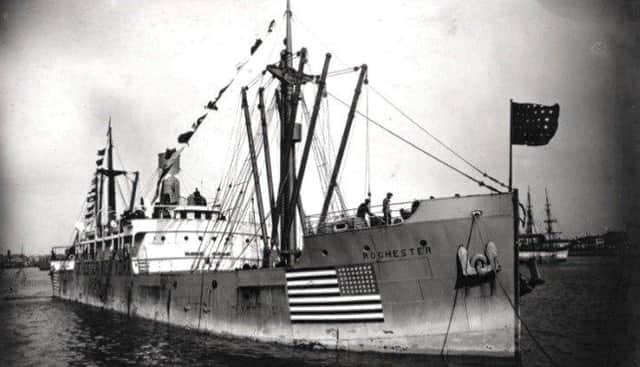

It wasn’t long before the local genealogist, who specialises in World War One, uncovered that Kokeritz’s ship, the SS Rochester, had been torpedoed by a German U-boat and that the Swedish-born mariner was buried in Derry’s City Cemetery.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“My head was full of questions,” says David. “Who was this captain and what was his story? I decided to visit the City Cemetery to find his grave and, maybe, his headstone might give me some clues. The lady at the cemetery office gave me a map with the grave position on it and, in no time at all, I was standing at the plot of the captain. But there was no headstone. Just a stretch of grass that covered a number of other graves which had no headstones either.

“So, I decided it was time to use all my genealogy skills in order to uncover the story of Captain Kokertiz.”

David was soon to unearth a remarkable story that, in 1917, dominated news headlines around the world - a story that, at the time, captivated the American and French public like no other. It was a story of courage, bravery, heroism and patriotic determination - all in the face of a resolute enemy who wanted to sink Kokeritz’s ship at all costs. Kaiser Wilhelm, himself, had put a price on the captain’s head. If the SS Rochester were sunk, America would enter the world’s first truly global conflict.

“I stood at Captain Kokeritz’s grave,” David recalls, “and told him I would tell his heroic story and get him the recognition he so rightly deserves.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

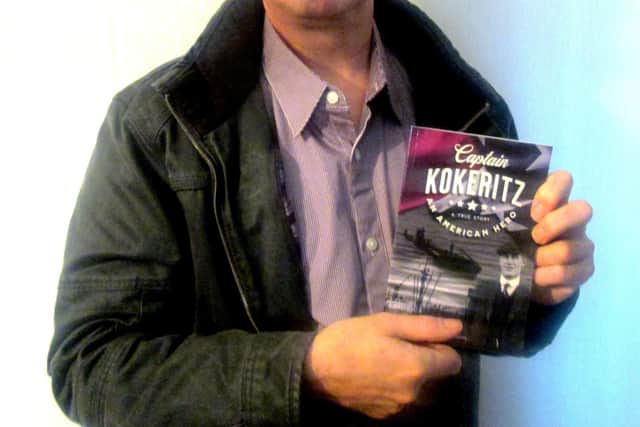

Hide AdAnd that’s exactly what David has done with the publication of a fascinating new book that chronicles the story. “Captain Kokeritiz: An American Hero” recounts a tale that, a century ago, had the nations of the world holding their breath as they awaited the outcome of a fierce battle of wills.

As David Jenkins relates, Erik Kokeritz’s war exploits kicked-off in early 1917 when two American shipping companies decided to challenge the Germany war zone by sending the first unarmed merchant ships to France loaded with provisions and machinery. The vessels were the SS Rochester and the SS Orleans.

Kokeritz, David’s book reveals, had been the first to volunteer his services to sail the Rochester from New York into the war zone and onto Bordeaux. On his arrival in New York to discuss the offer, he was warned not to take the ship. In response, he was reported as declaring: “The Kaiser and his war zone may go to a hotter climate than South America - I am to take my ship to France - Let’s go forward!”

As the two ships left on February 10, all of New York harbour stopped to cheer. The race was now on for the honour of being the first American ship to enter the danger zone. Days later, The ‘London Daily News’ reported on the ships’ progess. Its report said the whole of the American nation would be “straining its ears for news of their destruction or molestation. Should either come to harm... it will mean war.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn the morning of February 26, the Orleans was sighted off the French coast. The vessel was the first to make it across the Atlantic, going through the war zone and arriving at the mouth of the River Gironde on the western coast of France.

On Friday, March 2, three days later, it was reported that the Rochester had entered the Gironde estuary and later docked at Pauille where reporters made their way on board to interview Capt Kokeritz who said: “We entered the danger zone on Monday evening where I met only one sailing vessel and found not the least trace of any submarines. Thus, you see, it was not difficult for us to force the blockade and we have nothing much to be proud of in having reached port safely.”

On March 12, both captains were summoned to Paris where they received medals in recognition of their achievements.

A few weeks later, both the Orleans and Rochester made the return journey to the USA.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn April 2, 1917, America declared war on Germany in response to the rising toll in sunken American merchant shipping and civilian casualties.

In June, Kokertiz was again approached to take charge of the Rochester for a journey between New York and England. He agreed to do so. It was on August 5, 1917, that the captain left Baltimore on board the Rochester bound for Manchester on the north west coast of England. The vessel returned to Baltimore on August 22, with no incidents reported by the captain.

The next trip for the Rochester - now fitted out with a 3 inch gun on each of the fore and after decks, along with a machine gun at amidships - commenced on September 13. It was on the return journey, at the beginning of November, that the story of the Rochester took a fateful turn.

David Jenkin quotes Harry Yorke, messboy on the vessel, who later recalled a “terrific explosion” lifting the ship out of the water.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis account continues: “I was in the galley at the time conversing with the cook and he and I were hurled off our feet against the deck head, the lights in the galley going out at once and pots and pans being sent flying... The torpedo had hit us dead amidships.”

According to Yorke, with the ship sinking fast, Capt. Kokeritz “stayed long aboard obtaining necessary instruments, clothing and other gear and tried to ascertain how the men in the engine room had fared. As the boat seemed to be on the verge of sinking, he seemed to stay an agonising long time over these matters and loud calls were mde to him from the lifeboats. I began to think he had been overcome in the engine room. To our intense relief, he appeared at last, bearing in his arms blankets and coats which he threw down to the boats.”

The next few days - adrift in lifeboats in rolling, freezing seas - must have been nightmarish for the crew of the sunken Rochester.

In the captain’s lifeboat was Warren Brown Tompson, of the US Navy, who later described his experiences thus: “When the Rochester was struck, all we had on was the clothing we were wearing. I was in the captain’s boat along with 16 crew and five navy men... The cold was intense and the salt water which slapped over the boat was so cold that it penetrated through to the very marrow.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“After the fourth day, the fresh water gave out and for seventeen hours there was nothing to drink. Some of the men suffered so much from thirst and exposure that they cried out that they wanted to die and threatened to jump out of the lifeboat. They were held back by their shipmates.”

“Occasionally, we pulled on the oars to keep ourselves warm, but we were too weak from exposure and lack of nourishment to do much.

“Finally, when we were almost through, a British boat picked us up and it transferred us to a Red Cross steamship which landed us at an Irish sea port.”

David Jenkins writes that, when the captain and the surviving crew were brought to Derry, half of the men were taken directly to the City Infirmary with the other half going to the Sailor’s Rest which was run by the local branch of the British and Foreign Sailors’ Society. All were exhausted and suffering from swollen feet and legs as a result of frostbite.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter the captain had been attended to at the Infirmary, he immediately went to the Sailors’ Rest to visit the rest of his crew and, having satisfied himself that they were comfortable, he went to the City Hotel on Foyle Street where he was staying. After a full medical examination, an ill Kokeritz was ordered to his bed. By early February, his illness took a turn for the worst and, by the evening of February 3, he had lost consciousness. He remained in this state until he was confirmed dead the following morning by the owner of the City Hotel.

His death certificate states that he died of pleurisy. He was just 43 years old.

His funeral took place from the City Hotel to the City Cemetery on February 6, 1918 with full naval and military honours.The brass band and pipers of the 3rd batatallion of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, a naval detachment, and members of the Royal Irish Constabulary attended the funeral. The coffin was placed on a gun carriage and draped in the Stars and Stripes and Union flag.

Among those walking behind the gun carriage were the US Consul - owner of the captain’s burial plot - the Swedish Consul, the president of the Sailors’ Rest and the owner of the City Hotel.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDavid Jenkins is in little doubt that Captain Erik Kokeritz was a true hero of the First World War.

He concludes his book with the following tribute: “He was comparatively young in years when he died, but full of honour, having made great sacrifices with a heroism that will find an eminent place in the splendid annals of the sea.”

In total, 23 people died as a result of the sinking of the SS Rochester.