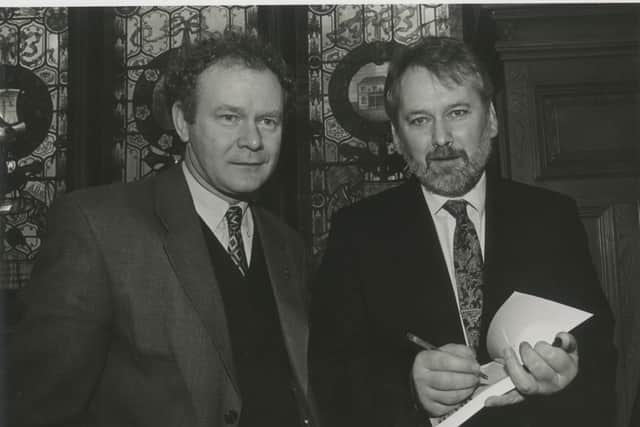

War Peace and the Derry Journal: Pat McArt on meeting 'The Boy General' Martin McGuinness

and live on Freeview channel 276

Shortly after I was appointed Editor a former priest, Paddy Logue, came to see me and said Martin McGuinness would like to meet me, and was it okay if he brought him down the next day? I replied I would look forward to it.

Back then if this was a Hollywood western, the director would have had Hume wearing a white hat – the good guy – and the baddie, who always wore a black hat, would have been McGuinness. So, I was intrigued to meet him.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThough still only in his early thirties. Martin McGuinness was already a living legend, mentioned in newspaper articles and books across the globe. For many he was a living Che Guevara. With his curly blond hair and piercing eyes, he had the film star looks that intrigued the media.

The background story of McGuinness is well documented. He left school early, ending up working in the local firm of James Doherty and Sons, Butchers. He didn’t get his 11-Plus, didn’t go to the elite local St Columb’s College, alma mater to Hume, Heaney, Friel et al, didn’t go to university and his world view of what was happening around him was very different to Hume’s.

While Hume was world famous for his peace efforts, McGuinness was world famous for his war efforts. I openly admit to being more than a little daunted at the prospect of meeting him for the first time.

My big problem was he wasn’t in the least like I had expected. Not even close.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe IRA terrorism chief, Martin McGuinness I met that next day and was to get to know well over the years totally threw a spanner in my world of stereotypes. McGuinness didn’t drink or smoke, didn’t mess around with women, had a lovely family and, I was to learn from empirical experience, kept his word. Well, to me he did. He came from what would be known locally as ‘respectable people’, his parents noted for their decency and their adherence to their Catholic faith. Both were not only daily mass goers but, I was told often, were also daily communicants.

McGuinness came to politics through the streets, through activism – not ideology. He told me this many times. And in an article written in 1988 – in his own handwriting and before the advent of the ubiquitous press release - for the Derry Journal, on the 20th Anniversary of the Civil Rights March of 1968, he explained it was the treatment meted out to nationalist leaders, people like veteran National Party leader Eddie McAteer, by members of the RUC that made him realise that they held all nationalists/Catholics in contempt.

He said that had changed him totally, that it was his road to Damascus moment, a seminal event in the life of a young man who grew up apolitical, ‘without a care in the world’ as he put it then, in Derry’s Bogside in the early 1960s. I remember almost verbatim what he said about it: ‘If they could do that to our leaders – people I looked up to, really no one in our community is safe or respected.’ Some months later the British army killed two young Derry men in highly controversial circumstances and McGuinness told me that was it - he made up his mind he was joining the IRA.

Despite his lack of formal educational qualifications McGuinness was highly intelligent. Indeed, all around he was way more complex than the box I had mentally tried to put him in. I had massive moral issues with him, and it took me a long time to adjust. How could I have come to not only like but genuinely respect a man who was regarded as a murderer by so many? How could such an obviously honourable man on a personal level lead an organisation that planted bombs under cars that blew people to bits?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo me it was a massive paradox, and it had my head in a spin.

The only explanation I can give is that we, literally, spent hundreds of hours talking over the years and the guarded conversations of our early days soon opened up to full on discussions where nothing was held back. I like to believe I got to know the real Martin McGuinness. What drove him was moral certitude. He believed totally in the righteousness of his cause, that we were engaged in a war with the forces of oppression and subjugation and that fighting that war was a just cause. He made no apologies. The forces of the British State were so massive, so superior, that the only way to fight them was, he told me, by using tactics that they liked to call ‘terrorism’.

‘How long do you think we would last if we fought a pitch battle with them?’ I recall him asking me one day, before he added: ‘We have to fight them on our terms, not theirs.’ And fight they most certainly did.

As a good Catholic boy brought up in a home where in childhood, we said the Rosary every evening, I had trouble for years finding the round hole in my brain in which I could fit this so-called ‘terrorist’ in a square box. I was far from alone in my dilemma. I saw and heard evidence of this over the years as Martin emerged from the shadows into political life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn the staff, there were some who clearly hero-worshipped McGuinness while others made clear their detestation. He was definitely a polarising figure.

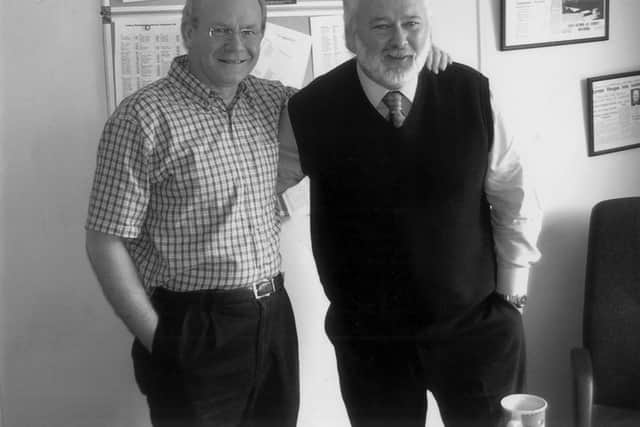

I can only state that in all my dealings with him over twenty-five years he was never less than honourable. In my dealings with him he was neither a thug nor a bully. Many were the heated arguments and debates I had with him and not once did he raise his voice or lose his temper. That’s a fact, something I, personally, can stand over.

*War, Peace and the Derry Journal by Pat McArt, published November 2023, is available from bookshops and colmcillepress.com, priced £20/€25.