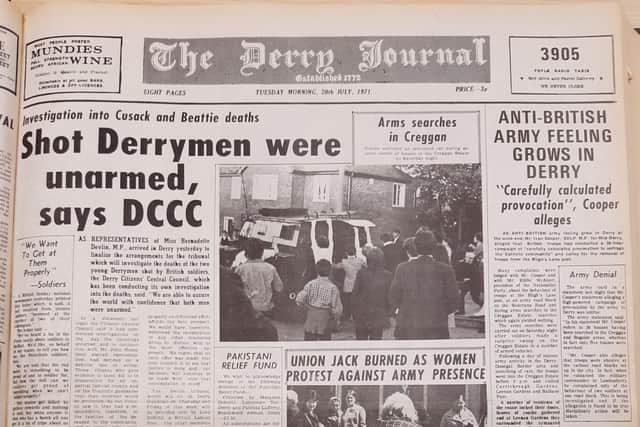

50th anniversary of Seamus Cusack and Desmond Beattie murders

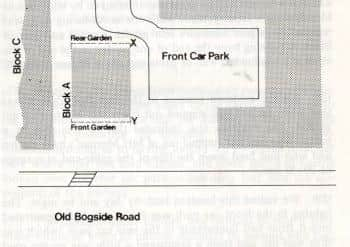

At around 1am on the morning of July 8, 1971, while rioting was taking place near the Little Diamond in the Bogside, Mr. Cusack was shot in the leg while he was standing in a garden in Abbey Park. The bullet had struck a main artery. He was rushed to Letterkenny Hospital where he died within about 40 minutes of having been shot.

Hours later during fierce street disturbances on the Lecky Road Mr. Beattie was shot though the chest by a member of the Royal Anglian Regiment. He died shortly after 3pm. Both men had been unarmed despite claims to the contrary by the British military. Seamus and Desmond were the first people gunned down by the British Army on the streets of Derry during the latter day conflict in Ireland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe city was plunged into grief and mourning by their deaths. There was an outpouring of solidarity with the men’s heartbroken families and a visceral anger over the behaviour of the British Army.

In the immediate aftermath of the killings SDLP MP for Mid-Derry Ivan Cooper said he had spoken to many eye-witnesses who were convinced that Cusack’s deaths was ‘cold-blooded murder.’

The Derry Citizens’ Central Council stated: “All reports confirm that both were unarmed, even by the wide definition of the British Army. It has been stated recently by the army in Derry, in response to a specific request from the Citizens’ Council for clarification that their fire orders had not been changed.

“On that occasion the Citizens’ Council made it clear to the army that orders to fire in ‘suspicious circumstances’ were not acceptable to the civilian population. The loss of two young lives in these circumstances has angered the city and demands an immediate inquiry by the responsible authorities.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe James Connolly Republican Club said: “The claims by the army that their victims were armed is only a deliberate attempt to cover up these murders.

“We demand an immediate withdrawal of the British troops from the Bogside area and also an immediate investigation into these murders.”

The North West Republican Clubs’ executive condemned the ‘brutal murder by British military of two citizens within the Bogside area.’

“It is quite evident to all that the tactics of the military are to indulge in the selective murder of Irish citizens within minority areas. No doubt we are witnessing now Stormont’s final deterrents to the minority’s demands for equality and justice.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Derry Nationalist Party said: “The British Army has embarked on a campaign of terror. But British terror tactics failed in 1921 and they will fail in 1971. The people of Derry will not be cowed by the 1971 version of the Black and Tans. Once again the blood of Irishmen is on the hands of tardy British politicians who do not yet realise that there cannot be a united Europe without a united Ireland.”

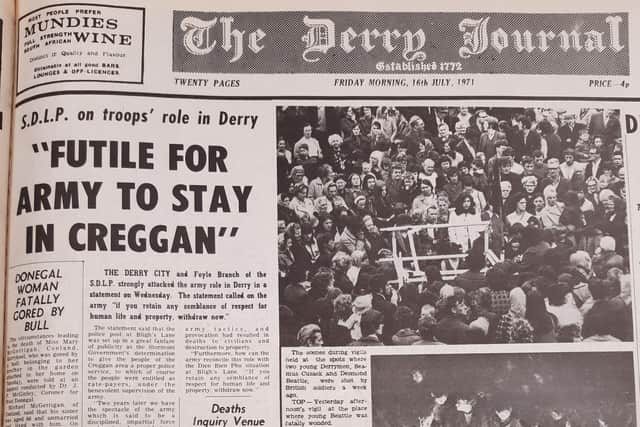

After the killings the SDLP attacked the army and demanded it withdraw from its position at Bligh’s Lane in Creggan.

“If you retain any semblance of respect for human life withdraw now,” the Foyle Branch of the party declared.

When news spread that Seamus Cusack had been killed in the early hours of Thursday, July 8, 1971, large crowds visited the spot in Abbey Park were he had been shot.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA black flag was flown there and on other buildings in the Bogside. A group of around 150 youths carrying a black flag marched to the British Army post at Victoria Market on the Strand Road where they started stoning the position. An army riot squad eventually emerged and the crowd retreated to the Bogside.

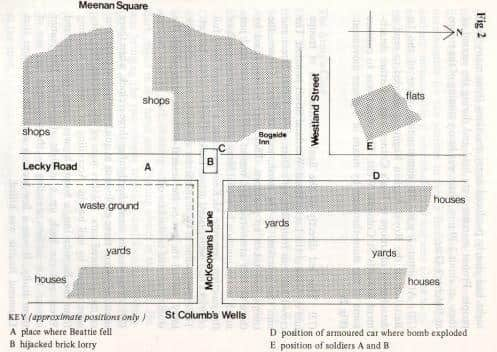

It was there near McKeown’s Lane on the Lecky Road that Mr. Beattie was killed.

The ‘Journal’ reported on July 9, 1971: “Eventually the army made a flanking movement as the crowd retreated into the Bogside and armoured vehicles and soldiers on foot moved through Rossville Street as far as Free Derry Corner - a further penetration than usual in these situations. During the discharge of rubber bullets by the army there was a loud explosion as a gelignite bomb was thrown close to an army vehicle, which was badly damaged at Free Derry Corner.

“The army reported that at this stage two soldiers were injured by nail bombs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Shots were discharged by the soldiers and it was at this time that young Beattie was fatally wounded. People in the area said later that gelignite and nail bombs were not used until the army firing had fatally wounded the youth.”

The British Army, in a statement, said troops were stoned in the Foxes’ Corner area between 3 and 3.15pm.

They said an ‘army land-rover was rammed by a civilian lorry which came out of the crowd’ and that ‘some nail-bombs were thrown at troops who immediately opened fire.’

The British military falsely claimed that ‘a nail-bomber was seen to fall and was dragged away by the crowd.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese were not the first deaths suffered in the north west during the conflict.

Francis McCloskey and Samuel Devenny both died in July 1969 after being severely beaten by the RUC. In June 1970 Thomas McCool (40), his daughters Bernadette (9) and Carol (3), and Thomas Carlin (55) and Joseph Coyle (40), died when a batch of petrol bombs prematurely exploded in Dunree Gardens.

And in February 1971 an 18-year-old Lance-Corporal of the 173 Provost Company William Joliffe suffocated from fire extinguisher fumes when the army vehicle he was travelling in was struck by petrol bombs on Westland Street.

But the killings of Seamus Cusack and Desmond Beattie marked a watershed in the course of the Troubles in that they were the first perpetrated directly by the British Army.

Derry was stunned by the twin killings.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt 5pm around a hundred girls marched from William Street to the Diamond.

“They bowed their heads as they passed the British Army post there. They then proceeded down Butcher Street into the Bogside and at the spot where young Beattie was fatally wounded they placed a small mound of stones.

“The roadway there was still blood-stained. The march was led by teenage girls carrying black flags,” the ‘Journal’ reported.

And late that night: “Hundreds of people gathered when the remains of Mr. Seamus Cusack arrived at his home at Melmore Gardens from Letterkenny Hospital. All the houses in the street hung out black flags and the family were recipients of numerous messages of condolence.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe British establishment’s response to the murders would become typical in the years that followed.

Robert Lindsay (Lord Balniel), the British Minister of State for Defence, speaking at Westminster on July 12, 1971, said: “In accordance with the standard practice, the Army has carried out its own investigation into the shooting incidents on July 8 and is satisfied that on both occasions when soldiers opened fire and civilians were hit the civilian concerned was carrying a weapon and there was good reason to suppose that he was about to use it offensively.

“This investigation does not supersede any proceedings that may be appropriate under the civil law, at which the Army will co-operate in making evidence available.”

To this the MP for Mid Ulster Bernadette Devlin responded: “On the one hand, the Army says that the people who were shot were threatening the soldiers with firearms at that time, but Mr. John Hume in Derry, the Member of Parliament for that area, says that he has evidence which he is prepared to bring forward to an inquiry to say that that is not true. The only conclusion which can be drawn is that the Army will not face a public inquiry and will not face the facts. Therefore, the Minister of Defence stands in this House today as the official liar for the General Officer Commanding NI and about the murder of people in the city of Derry.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAn independent international inquiry into the killings was presided over by Anthony Gifford, Q.C. (Lord Gifford) in the Guildhall. Paul O’Dwyer, the Irish-born American attorney whose brother William had served as Mayor of New York in the 1940s, and Albie Sachs, the ANC activist who later survived being blown up by the South African security services in Maputo, Mozambique, in 1988, were both on the panel of this unofficial inquiry which was shunned by the British Army and the RUC.

Their report flatly contradicted British claims.

In respect of Mr. Cusack they stated: “We concluded that the eye-witnesses made out a massive and compelling case that Cusack was not armed with a rifle at the time he was shot. Our finding in this regard is supported by a number of circumstances which taken individually might not have been too convincing but which viewed cumulatively carried considerable weight.”

The report did accept that nail bombs were being thrown at the British Army from the vicinity of a hijacked brick lorry near McKeown’s Lane when Mr. Beattie was shot. But the panel were equally convinced that he was not armed.

“Although we do not know what Beattie was doing in the vicinity of the lorry before he ran down Lecky Road, we are satisfied on strong probabilities that he was not the man who was about to throw a bomb. This being the case, there is no other evidence to suggest that he was carrying a bomb, or threw a bomb, or used any other such lethal weapon.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe deaths of Seamus Cusack and Desmond Beattie were followed by a significant escalation of violence in the city. This was exacerbated by the introduction of internment without trail in August of 1971 which sparked an uprising within nationalist areas. A week after the killings the SDLP said that it was withdrawing from Stormont.

It said: “The SDLP issued a statement earlier this week in which we demanded an impartial inquiry into the deaths of two young Derry men resulting from British Army action, and in which we made it clear that in the event of failure by the authorities to agree to our demand we would take a certain course of action.

“Our demand has not been met and we have therefore no alternative but to pursue the course of action that we have already outlined.”

Four more civilians would die at the hands of British soldiers in Derry that year. They were Hugh Herron (aged 31, shot dead by the British Army on August 13), Annette McGavigan (aged 14, shot dead by the British Army on September 6), William McGreanery (aged 43, shot dead by the British Army on September 15) and Kathleen Thompson (aged 47, shot dead by the British Army on November 6).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEamon Lafferty, aged 20, became the first IRA Volunteers to be killed in the city when he was killed in a gun battle with the British Army in Creggan on August 18, 1971. Another IRA Volunteer Jim O’Hagan, aged 16, died in what appeared to be an accidental shooting the following day.

Prior to the deaths of Cusack and Beattie and, subsequently, the introduction of internment without trial, no British soldiers had been killed by republicans in Derry. That year eight soldiers would be killed as the violence escalated: Paul Challoner (aged 23, shot dead by the IRA on August 10), Martin Carroll (aged 23, shot dead by the Official IRA on September 14), Roger Wilkins (aged 32, shot dead by the IRA on October 11), Joseph Hill, (aged 24, shot dead by the IRA on October 16), David Tilbury (aged 29, blown up by the IRA on October 27), Angus Stevens (aged 18, blown up by the IRA on October 27), Ian Curtis (aged 23, shot dead by the IRA on November 9) and Richard Ham (aged 20, shot dead by the IRA on December 29).

Gifford stated: “The bulk of this report was written before the internment decision and its terrible aftermath. The fierce battles of these past months have tended to overshadow the shootings of Cusack and Beattie in July. Yet the deaths of these two young men were no less tragic because they were followed by more deaths, and the lessons to be learnt have been underlined rather than erased by the subsequent events. The internment decision was not taken suddenly; it followed a succession of incidents, in which the various conflicting groups in NI grew further and further apart. It is indeed arguable that the failure of the authorities to deal effectively, openly and candidly with the public protest and controversy which succeeded the shootings in Londonderry of July 8 was a major factor contributing to the escalation that followed.”