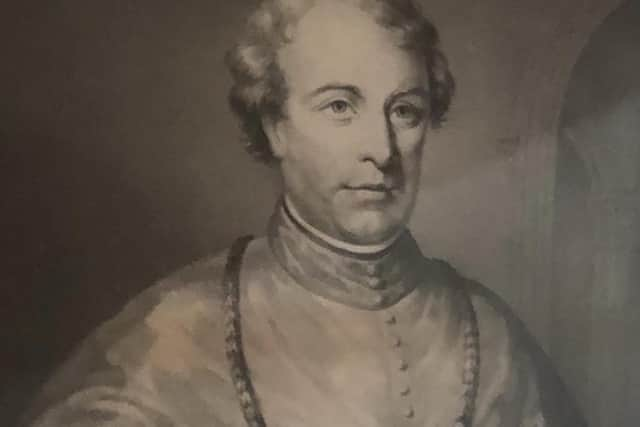

An Gorta Mór: Bishop Maginn: The Road to Derry (Part 1 of 2)

and live on Freeview channel 276

In the realm of humanitarianism, few figures shine as brightly as Bishop Edward Maginn. Born into humble origins in Fintona, County Tyrone, in the waning days of 1802, Maginn's journey from the fields of his father's farm to the corridors of power in Derry is nothing short of remarkable.

Maginn's formative years were spent in Buncrana, County Donegal where his family had sought a better life. It was there that he imbibed the teachings of the Catholic Church, steeped in a tradition of service and sacrifice. The young Maginn, imbued with a deep sense of duty, set his sights on the priesthood. In 1818, he embarked on a transformative journey, enrolling at the Irish College in Paris to pursue his theological studies.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

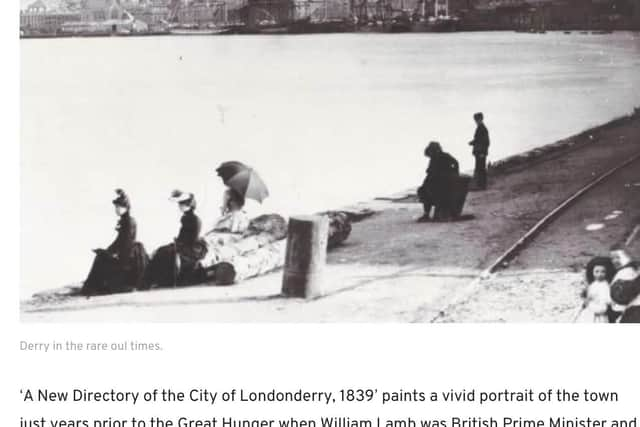

Hide AdThe Catholic Church in Derry, scarred by a long and tumultuous history, had weathered the storms of persecution and destruction. Saint Columba, the missionary monk from County Donegal, had left his indelible mark on the region, founding a monastery that stood as a testament to the faith. But the ravages of time and the forces of conflict had taken their toll. An Teampall Mór, the majestic diocesan cathedral, fell victim to the rampages of English forces in the 1560s, transformed from a symbol of spiritual solace into a grim storehouse for gunpowder. Its eventual ruin was sealed when Sir Henry Docwra and his army swept into Derry City, employing its stones to fortify their newfound bastion.

Yet, amidst the ruins and remnants of a fractured past, the Catholic community endured, bound together by the unyielding thread of their faith. The Penal Laws, an insidious web woven to suppress the rights of Catholics, sought to stifle their voices and suffocate their aspirations. Catholics in Derry faced restrictions until 1720, and it wasn't until the Emancipation Act of 1829 that they could consider constructing a cathedral again.

Daniel O'Connell, the charismatic leader of the Catholic Association, rose to challenge the chains of oppression and demand the emancipation of his people. Maginn, an ardent supporter of O'Connell's cause, lent his voice to the clamour for justice, denouncing the injustices perpetuated by the local magistrates and fervently advocating for the repeal of the Union with Great Britain, a union that had shackled Ireland since 1801.

The Association gained immediate traction, and O'Connell drew crowds of over 100,000 to his rallies. His popularity carried him to a County Clare by-election victory in 1828, making O'Connell the first Catholic to win a seat in the British Parliament in more than 100 years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter Emancipation was granted in 1829, Maginn played a significant role in the restoration of the Catholic Church in Ulster. His ordination in June 1825 marked the beginning of a remarkable chapter in Maginn's life. As a curate in Moville, he tended to the spiritual needs of his flock, but his gaze was fixed on a higher purpose. The plight of the impoverished in Donegal's northwest stirred within him a burning passion to effect change, to lift the burdens that crushed the hearts and bodies of his parishioners. It was this relentless drive that caught the attention of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, leading to his appointment as the administrator of the diocese of Derry in August 1845.

Maginn's rise through the ecclesiastical ranks, culminating in his appointment as coadjutor to Bishop John McLaughlin, coincided with a pivotal moment in Irish history. The ailing health of his predecessor thrust him into a position of immense responsibility, charged with guiding his flock through the treacherous waters of political and social upheaval. The Great Hunger, a catastrophic famine that would decimate the population and scar the collective memory, laid bare the inequalities and injustices that festered beneath the surface. However, Maginn, with an unwavering commitment to his people, demonstrated his vision and ambition for the diocese of Derry.

His plans included the construction of six new churches, the confirmation of 11,000 adults and children, and the groundwork for a seminary on Pump Street that would later become St. Columb's College. Maginn actively participated in nationalist politics and served as the inspiration behind the Monster Repeal meeting at Carndonagh on 7 August 1843. His letters on land use and the administration of the Poor Law, as well as his testimony before the Devon Commission on land ownership, provided valuable insights into the social conditions of Ireland in the first half of the nineteenth century. In 1844, he provided evidence before the commission, proposing land reform through the establishment of an independent district estate evaluator and compensation for tenant improvements based on the duration of the lease.

Within a short period, Maginn became a controversial figure. However, as the potato blight struck Ireland for the second consecutive year, his focus shifted to more pressing matters. The impact of the second failure was swift and devastating, resulting in three-fifths of the country's food supply disappearing and three million people facing dire circumstances. The new bishop found himself confronted with urgent priorities across Derry and Donegal, where tenants faced eviction, homeless individuals perished in ditches, and famine-related diseases spread. It was often local priests and ministers who stood on the front lines, tending to the most vulnerable members of the community.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn a letter to the editor of the Derry Journal dated 19 December 1846, a member of the Buncrana Relief Committee wrote:

‘The clergymen here are unable to attend to the dying or bury the dead. Night and day, they are rushed from one place to another, providing religious solace to those whose lives could be saved with food. Yet, despite the nine-week-old presentment sessions in Buncrana, there hasn't been a single person employed in public works in this area. The famine victims, summoned before their Creator, can find solace in knowing that they are not accused of injustice toward the landowners, as they paid their rents with the little they had for their own subsistence.’

In early 1847, Bishop Maginn grimly reported, ‘In the diocese of Derry, we have a Catholic population of 230,000 souls. Of these, at the present time, there are at least 50,000 in actual starvation.’

Part 2 will feature in next week’s Derry Journal.