The Derry man who locked the gates of the world’s first open prison

and live on Freeview channel 276

In the mid 1800s, problems began to emerge as regards criminal prisoners being transported from Britain and Ireland to the colonies.

The administrations of the colonies (with the exception of Western Australia) had decided to stop receiving criminal prisoners due, in part, to the emergence of pressure groups which thought Australia, in particular, was being given a bad reputation because of its high criminal population.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA solution was required and, so, in 1853, an Act of Parliament was passed which resulted in convicts under sentence of transportation instead discharged at home on ‘tickets of license’. In practice, it was said the public found that convicts at large on license were frequently in a most unreformed condition which made it difficult for them to be received into the labour market and, as a result, many resorted to criminal behaviour.

At this time, former magistrate, Sir Walter Crofton, took an interest in reform of the penal system. This led to his appointment, in 1853, as a member of a commission to inquire into the state of Irish prisons and the following year he became chairman of the new Irish Convicts Prisons Board. Sir Walter came up with a three-stage system of confinement which emphasised training and performance as the instruments of reform.

The first stage was a period of solitary confinement. This would take place at Mountjoy Prison, Dublin, where prisoners would be kept for long periods in their cells and were not allowed to communicate with other prisoners or staff. This period lasted for approximately nine months.

The second stage involved communal labour and took place at Spike Island, Co.Cork. The performance of the prisoner would be continually accessed. A marks system was put in place - the better the performance and conduct, the more marks the prisoner would receive. Once they had achieved the required number of marks, the prisoner could be moved onto the third stage where they could demonstrate their dependability and employability in the outside world. The release of the prisoner was conditional on their continued good conduct. When released, they were issued with “tickets of leave” and placed under the supervision of an inspector who verified their employment status and made unannounced visits to their place of residence. This third stage took place at Lusk, Co. Dublin and Smithfield, Dublin City.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1856, a parcel of land, known as Lusk Common, had been purchased with two iron huts built to house the prisoners. The site would become a farm (known as Lusk Prison Farm) with prisoners taught how to manage and grow different crops, how to use farm machinery and look after farm animals. At the end of each week, prisoners would receive a small payment for their work. The number of prisoners held at Lusk at any given time was between 30 and 40.

What was very noticeable at the Lusk site was the absence of prison walls. Nowhere in the world had ever tried this three-stage system before and it was an experiment that attracted interest from governments across Europe and, even, America.

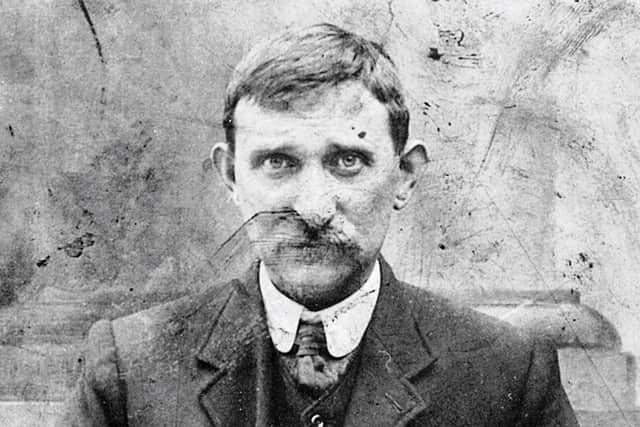

My great grandfather, William Alexander Jenkins, had become a prison warder in April 1882. In July 1883, he moved from his post at Mullingar Prison to Lusk Prison Farm.

William Alexander was born i nJuly 1854 at Bonds Hill, Waterside. When he was six years old, his father and two brothers died of illness. He and his mother then moved from their Waterside home to her father’s farm outside Claudy. William Alexander attended Learmount National School in Park Village. In 1872, he became a Royal Mail messenger boy for the Claudy and Park area and delivered mail on horseback. His first wife, Mary Anne, died of TB in 1880 at their home on Workhouse Row (Glendermott Road) and he remarried, in 1882.Because of his experience with horses, the prison authorities thought he would be very well suited to looking after the working horses at Lusk Prison Farm. William and his new wife lived in a small cottage within the prison boundary. Four of their 16 children were born at the prison.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe land in and around Lusk Prison Farm was drained by the prisoners to allow crops such as potatoes, cabbages, carrots, oats and wheat to grow. Milking cows were kept along with sheep and pigs whose offspring were sold at local markets as well as being transported to Dublin Port and shipped to Britain. The crops were used to feed the prisoners and staff at Lusk and were also sold at local markets. The Dublin City prisons were sent any surplus produce. A school instructor visited the prison every evening and taught prisoners to read and write along with other life skills. On Sundays, prisoners were taken to the nearby Catholic and Protestant churches. The local population seemed to tolerate having prisoners living near to them.

The three stage system set up by Sir Walter Crofton was seen as a success by most prison reformists and lead the way in the development of parole systems in Europe and America. But the system had its critics and public pressure groups demanded tougher regimes in the prisons. MPs also considered the system too expensive to run.

In the end, the critics got their way. It was announced that Lusk Prison would close on December 31, 1886 with its prisoners sent to Maryborough Prison (now known as Portlaoise). William Alexander, along with another warder called Daniel O’Connell, stayed on the prison site to manage the day to day running of the farm. They employed local labourers to help them with the crops and animals.

In September 1888, all produce, animals, machinery, prison furniture and fittings were sold at auction. Two months later, Warder O’Connell fell ill and had to return to his Portlaoise home. This left William Alexander to look after the site until all items that were listed at the auction had been sold off. In January 1889, he closed Lusk prison gates for the final time. He was then sent to Mountjoy Prison where he worked as a warder until 1902.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWilliam Alexander was then sent to work at Maryborough but suffered astroke in February 1903. Due to his ill health, he was pensioned out of the prison service and, in 1904, he and his family returned to Derry and lived at York Street in the Waterside. He was unable to work due to his continuing ill health and died at his family home on November 17, 1907, aged 53.