War, Peace and the Derry Journal: Let's begin at the end

and live on Freeview channel 276

It is a strange way to tell a story but let me start by telling of my last day at the Derry Journal. It was a bitingly cold, gun-metal grey kind of day, a Monday afternoon at the end of February 2014, when I walked out the door for the last time. Clichéd as it sounds, the weather matched my mood.

I had made the decision earlier that I would leave quietly, so I slipped out on the pretext I was off to get a cup of coffee from the wee huckster shop across the road and I didn’t come back. I didn’t need the fuss of another ‘leaving do’– photographs, speeches, long goodbyes. I already had all those years earlier – back in 2006 – when I had retired as Managing Editor.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAgainst the biting wind I started walking. I was, now that I think about it, almost in a daze. Just a few hundred yards from the Journal’s brand spanking new hi-tech offices at Duncreggan Road I soon passed the old Journal building on the Buncrana Road where I had spent my entire career as Editor. I instinctively stopped. I knew this was important to me psychologically, that I needed to take cognisance that something that had been a major part of my life was over.

As I gazed at that old building, now isolated and in total darkness, I found it all but impossible to believe it was being used as a storeroom for a supermarket. To me it was a kind of sacrilege. The times, the craic, the memories we all had of that place made it almost sacred to me.

The mind is a strange thing in that I knew instinctively I needed to take stock, to rationalise what was happening as I faced into a very different future. Standing there I remembered the many times the icon that was John Hume had come down and outlined what was happening politically. Many were the rows we had too in my office. A political giant, and a man with a brain the size of a planet, ‘Saint John’ could, I often found, be a difficult person to deal with if you diverged from his viewpoint.

I had a flashback too to the day I got into an argument with IRA leader, Martin McGuinness and told him to f**k off.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was a huge day for Derry when Garret FitzGerald became the first serving Taoiseach to visit the city, and he brought a huge entourage to the ‘Journal’ - we were the centrepiece of the visit – in the mid-1980s. Politically, that was a real big deal, significant in that it told us that change was, finally, in the air, that Dublin was getting a role in Northern affairs.

Despite the Troubles and the danger, British army officers used to call in regularly to that building. In the main they wanted to have a chat about how the nationalist people were feeling, and to see if they could improve their image and/or reputation with the local populace. God bless their little cotton socks as I had to tell more than one naïve officer that, after Bloody Sunday, lifting water with a net would have been easier than improving their PR.

It’s a ridiculous thing to have to admit now but, as the troubles had ensured tourists were few, a non-Derry accent in those days was an absolute rarity - so having these guys with their upper crust accents in the office always added a bit of colour to an otherwise run-of-the-mill groundhog-type day. It was so unusual.

Away from all that, I recalled too a person who I can only describe as deranged standing outside my window, mouth frothing in his rage yelling ‘I am going to fucking kill you’. He had wanted some hare-brained article published, and after many subtle attempts to let him down gently, to tell him it wouldn’t be happening, I had to take a stronger line when asking him to get out of the office. He then went totally ape.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnother of this ilk landed late one night off his head on something I suspect was much stronger than alcohol, threatening similar retribution if a story about his son appeared. With the help of a couple of colleagues I physically removed him. I didn’t take him seriously though. I should have, as last I heard, he was actually serving time for murder.

And, of course, there were the inimitable members of staff. God, what an array of brilliant characters.

Amongst these were Domhnall MacDermott who, tragically, died in his 30s. He was a true intellectual, enjoyed a very hectic social life but never missed a day at work. He had such good contacts in the Republican Movement, he got more important stories during the Troubles than any reporter in the country.

And then there was Siobhan McEleney, a lovely woman, devoted mother of four wee girls, who was the Deputy Editor for many years. Siobhan died of a brain tumour in her 40s. She was a one-off, irreplaceable. She often comes into my mind to this day. Most people in the North-west will still remember Larry Doherty, the chief photographer who, thanks to the Troubles, his hard-working, fearless nature, and the massive global demand for photographs of the conflict, could afford a house on the Culmore Road and a boat on the Swilly.

All that and more hit me that day.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMost people have heard the old saying that when you are dying your life flashes before you. That day standing in the howling wind outside that now lifeless building I was given a sort of premature version of that. It might sound more than a bit on the dramatic side to suggest this but I had lived a sort of vicarious life few journalists got to experience, dealing with events and people where it was often, quite literally a matter of life and death. And I wasn’t always a spectator on the side lines, I was centre stage for so much of it. Now it was all over.

My life, I knew, would never be the same again.

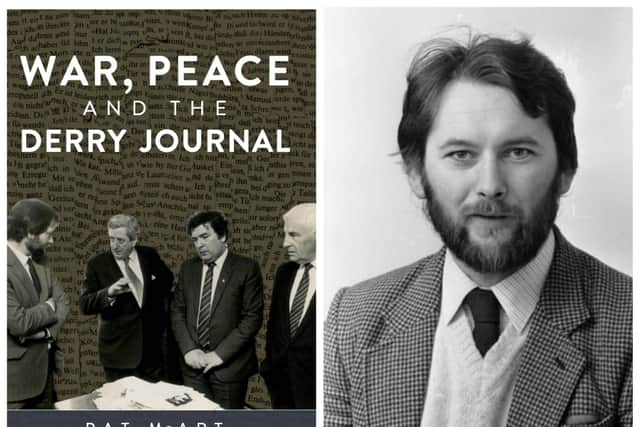

*War, Peace and the Derry Journal by Pat McArt, published November 2023, is available from bookshops and colmcillepress.com, priced £20/€25.