Fear and loathing... Derry in the Viking age

The Vikings of Norway, Sweden and Denmark were rowing down the Atlantic from their coldlands; the invasion force of about 100 longships were coming to the relatively warm climate of the Doire area, with its plains around the ancient monastic site. Ireland was the Island off Saints and scholars while the Vikings were barbarians. This mass exodus from Scandinavia was perhaps due to pressure of population in the fjords or large sea inlets of these northern kingdoms. The longships were up to 70 feet in length and historians have grouped them altogether as the Danes.

They had rowed up the River Foyle where there were ancient forts or duns ruled over by a rí or ‘king’, who were devout Christians. From the River Foyle they made their way inland to the Sperrin Mountains area with its many forests, where there were many more groups of Christians with monasteries almost certainly made out of wood. But the Danes were mainly a seafaring race and most of their settlements were along the coast - first of all at Doire, then along the Antrim coast to Laharna or Larne where they called Larne Lough as Ulreck’s fjord. Other settlements were established at Strangford (fjord) and at Carlingford (fjord) from where they raided along the southern Irish coast.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was now 400 years since the age of Saint Patrick in Ireland, but now the Norse threatened the existence of the Gaelic church. Many Danish sites around the Foyle were named after Danish leaders, having put to death a large number of Christians or having captured slaves to be sold back in their homelands.

But in the Derry and Foyle areas the Danes were not overthrown until the 11th Century with their containment at the Battle of Clontarf by the High King off Tara who was a Christian, having been converted to the faith.

The longships could move quickly over the waves, each ship made up off about 30 warriors straining at the oars. The ships were propelled by both sails and oars, with a pagan motif at the prow along with a sea king, the sails having a variety of colours. But the Danes in Foyle had not only come to conquer, they were farmers and settlers, some of them falling to the level o the native Gaelic, who could only fight with leather shields and stone swords. The plains around Derry or Doire had rich agricultural lands, along with many little churches and some monasteries, smaller than that of Saint Columba’s foundation. The Norse had heard in their homeland that there were great riches to be won in the kingdoms like that of Aileach and elsewhere in Ireland and in Britain, where they established themselves at Jorvick or York, the headquarters off the Viking operation in the British isles.

These dark haired and light haired pagans with cloaks and shields were intent upon stealing from the Church with its many monasteries and churches. Ireland was not a very populous country, which made the task o the Vikings that much easier in regard to conquest. From the River Foyle the fierce viking sea king Turgesius went forward to plunder much of what is today County Londonderry or Derry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIreland was not alone in the Norse itinerary for they were raiding as faraway as Constantinople (Mecklesburg) in the 9th Century, which had much wealth and capital; and of what remained in the Roman empire in the east of Europe, West Rome having fallen to the barbarians by the 5th Century with the attacks of the Huns and Goths.

The monks of Aileach and Doire wanted to preserve and hide their riches from the Danes, for which purpose they built round towers, the monastery at Derry having been raided a number of times. Upon hearing of an attack, the monks at Doire climbed into their towers, carrying their riches with them. The Danes put the monks to the sword and set up a statue to Odin in the monastery, smashing or burning statues of Christ and the Virgin Mary; they also desecrated the altars in the Doire churches.

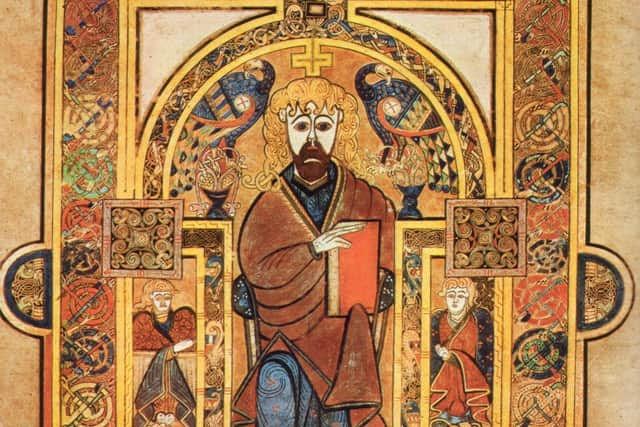

But the Christians could never respect the Vikings, even though over the centuries many of them became Christians. Now Turgesius was put to death by drowning in Lough Owel by some of the Gaels that managed to get on top of the Vikings, a similar fate awaiting other Norse. Although the monks of the Foylelands were burdened by the Danish wars they were still able to pen these beautiful manuscripts or books of the Gaelic monasteries in the 8th Century, the age of the Tara brooch, the Ardagh chalice and the Book off Kells, three of the world’s treasures. Metal workers beat out their bronze, silver and gold chalices, crosses and many other works in curves of gold wire incised with lines. The colours off the penmen were produced in enamel work, and the mason would cover the shaft with curves painted on it. The plate of these small crosses would have been held together by nails. Thus, at the edge of the world, in a Europe that was recovering from the fall of ancient Rome, the kingdom of Down were experiencing a great age of art and learning - the island off saints and scholars. During times of peace, scholars arrived in the Foyle banks to learn all about the Gaelic church. In the Church of what is today County Down the monks kept alive the Christian spirit, and also travelled to Europe to bring the word to the court of the German emperor Charlemagne in the 9th Century.

The people of the Foyle plains always lived in the hope that the Vikings would be defeated and that the faith of the Gaelic Church would last forever in the Emerald Isle and beyond. Although the Gaels made no united effort to fight the Norse, the local Gaelic chiefs managed to intercept their murderous raids and killed them mercilessly. The round towers of Ireland are the chief remains of Gaelic Christianity in the island and still dominates the landscape, usually connected with a monastery, some of them standing alone. They are a tribute to the architecture off the age, but it is not clear when they ceased to be places of refuge. In closing, the Gaelic for Gaelic for round tower was clog teach, a bell tower, the plural being clog tigh.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdToday, there is a little Viking blood flowing in Irish veins.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael Sheane is the author of several books on Irish history, most of which remain in print. He was born in England in June 1947 and brought up on the Antrim Coast, where he lived until 1999 before moving to Antrim. He was educated at Larne Grammar School and at Orange’s Academy, Belfast and attended Trinity College, Dublin.

So far he has written and published 28 books on the history and politics of Northern Ireland. His latest book is ‘Patrick, a Saint for All Seasons’. He contributes widely to local press , radio and television on Ulster affairs. His books published by Arthur H Stockwell Ltd. include ‘Ulster in the Viking Age’, ‘Ireland’s Holy Places’, ‘The Great Siege’, ‘The Twilight Pagans’, ‘Saint Patricks Missionary Journeys’, with his latest work ‘The Problem of the Two Patricks’ in preparation. For more see www.ahstockwell.co.uk/history