The Derry Journal’s story mirrors the history of local people

and live on Freeview channel 276

Nor could this lively Presbyterian publisher have dreamt of the significant part the Journal would play in the lives of generations of local people, less still that it would undergo a radical transformation into a voice for nationalists following a succession of political earthquakes that changed the course of Irish history.

The Journal’s first edition was published on June 3, 1772 in Mr Douglas’ own commercial premises in the Diamond area of the city centre. Already an ancient city by then, Derry was a vibrant and important port of trade and commerce, with a booming shipping industry and a fledgling linen industry, would be a precursor to the textile factories that over the next two centuries would provide employment and a source of income for hundreds of thousands of local women and men over generations.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLittle over a century on from the Siege of Derry, the city in the 1770s was on the surface a much more settled place, were trade was thriving and markets held in the Town Hall Exchange, then located on the Diamond. The colourful Bishop Frederick Augustus Hervey had been installed as CoI Bishop of Derry, taking up residence in what is today the Masonic Hall with its sprawling gardens (now Bishop Street car park). It was this Bishop who built Downhill and the famous Mussenden Temple on a cliff overlooking Benone and Lough Foyle, and who is perhaps most noted for his conciliatory stance towards the native and largely Catholic population of the wider region. While St Columb’s Cathedral was already completed and well established within the City Walls, the foundations of St Columba’s Long Tower Church would be laid 12 years after the Derry Journal was founded.

The church project was spearheaded by Dungiven native and local priest Father John Lynch who lived off Ferguson’s Lane. The Catholic Bishop of Derry over this period was Fahan native Dr Phillip McDevitt, who was installed six years before the Journal was founded, and lived in Moville and also in Clady outside Strabane, as detailed on the Long Tower’s website. In a cross-community gesture, the Protestant Bishop Hervey donated £100 to the construction of the Catholic Long Tower Church, which was built on the site of a once massive cathedral for the Templemore parish beside an ancient round tower, with links back to the 6th Century and St Columba.

Ireland had been a dangerous place to be a Catholic cleric in the 18th Century under the violent suppression of the Penal Laws. Indeed, people could and would be persecuted, hunted and killed just for performing Mass, including Moville native and Fahan parish priest Fr James Hegarty, who earlier in the 18th Century was beheaded and buried in Buncrana’s shores at the place still known today as Fr Hegarty’s Rock.

While there was widespread poverty at the time for the more affluent, life continued as it had. Boom Hall in 1772 was acquired and rebuilt by James Alexander (who would later become MP for Derry and whose descendant would marry Cecil Frances Alexander) along with lands at Moville, while Prehen House was in the possession of the Knox family, and Elagh Castle- once a stronghold of the O’Doherty clan - was by now already in ruins. It’s tower can still be seen today high above the Buncrana Road near the border with Bridgend.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBeyond the bustling streets of Derry’s commercial hub, tensions were boiling here as they were elsewhere across the world however towards the end of the 18th Century. Revolution was in the air. Across the water in England, King George III was about to experience a series of disasters in the New World, with revolts against taxation and the Crown leading to the American Declaration of Independence in 1776. The following decade would see the French Revolution and subsequent execution of King Louis XIV and Queen Marie-Antionette. Here in Ireland, the disenfranchised and dispossessed Irish native population and Protestant dissenters were beginning to organise themselves in various forms once more as the cause of national determination slowly rose to the fore. And it was in this climate that Wolfe Tonne, who rose to the fore.

The course of the next 200 years of conflict, resistance and trouble need not be rehearsed here, but the Journal was there through it all, documenting the various twists and turns of international as well as local affairs, and itself coming out in support of Catholic Emancipation. Indeed a century after its foundation - as the history of the Journal further on into this edition details- the paper adopted an Irish nationalist editorial stance and dropped the London prefix from its name.

The Journal bears a number of distinctions and has a long and proud history of serving the north west region. The imposition of a border never changed that and a century of from Partition the Journal today still serves of the populations on both sides of the border in the north west.

In so many ways, the Journal is the story of the people of the north west, their stories, their triumphs and tragedies, listing even in its early editions the many who left Ireland on board a ship at Derry’s docks in search for a better future for themselves and the families back home they might send money to if they found work, relatives generations of them would never see again. In spots across Inishowen and other areas, there are still mounds of rocks today, which as some of you will know are very special. These are the rocks people brought each year to specific sites to represent their loved ones far away, the local people who had made that voyage out to an uncertain fate, often with little or nothing to their name. The diaspora of Derry, Donegal and Tyrone and indeed the rest of Ireland have been a powerful support to people back home over the centuries and people here in turn have never forgot them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe arrival of the internet has enabled us to stay in touch like never before, and it is great to see people around the world with connections to or from here reading the Journal online or subscribing.

Like many of you, I grew up with the Journal, and like many of you I have featured in it several times while growing up. From my Primary 1 class to secondary school pictures, Derry Feis photos, being nabbed for a vox pop on the street, school formal pictures and graduation. The giant Friday Journal is where I found my first flat, where I looked for the cheapest cars I still couldn’t afford in the Classifieds, found out what was on that weekend. The Journal has been part of life here for generations, even hosting dances in times gone by.

My Journal story

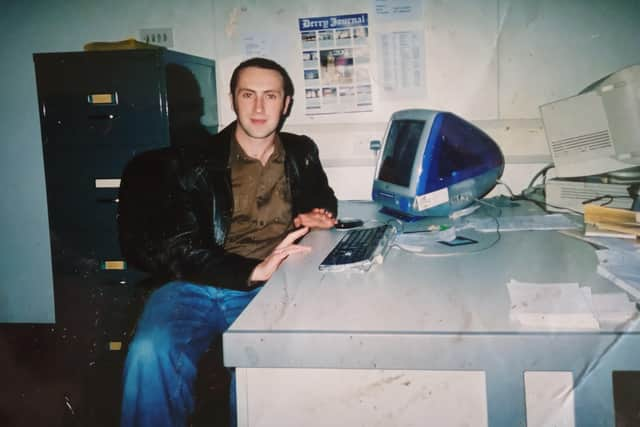

I started working as a junior reporter in the Journal as a 22-year-old, after finishing a degree in Liverpool followed by a Journalism Course at North West Institute of Further and Higher Education, tutored by lecturers including Suzanne Rogers, Kevin Logue, Christine Mitchell, a course which has set generations of local people on media career paths. I had worked shifts elsewhere and had applied before unsuccessfully but the Journal was always the paper of record in these parts and I was glad of a full-time job there. It was 1999, a year after the Good Friday Agreement, and this was in Buncrana Road. There was a raft of us who came in around that time, Erin Hutcheon, Claire Allan, Eamonn Houston, Ian Cullen and Linda McGrory among them. It was a busy and big open planned workplace, with various departments all working alongside each other. I have great memories of being there over those three years, and how kind and generous many of the more experienced staff members there were. We learned a lot from them. In life you always remember the people who helped you, people who genuinely care about other people, be it a teacher, colleague or mentor, and I’d like to acknowledge here the late Siobhan McEleney and also Mary McLaughlin, Arthur Duffy, the reporters, photographers, production and office staff from the Journal who went out of their way to help new recruits like us find their feet and understand what the Journal was about.

I was there when the internet arrived, when the first mobile phones were handed out, when Derry rang in a new Millennium to ‘The Final Countdown’ in Guildhall Square, I was there when 9/11 happened. It was a different landscape and as then Editor Pat McArt often reminded us, stories didn’t walk in on legs any more. I remember trying to come up with ideas for different features, including staying in reportedly haunted local places overnight and ending up terrified at one particular location. We were young, new and would try anything. And we had a steady wage (not much admittedly, you’ll never be rich in this game, but it was something). I decided to save a bit and follow in my brother’s footsteps and go travelling to far flung places and left the Journal in late 2002. I wouldn’t return here until 2014 and despite having worked numerous jobs since my mid-teens, in chip shops in Creggan and Rosemount, as a cleaner, an invigilator at exams, in a hostel, fruit-picking, call centres, off-licenses, Desmond’s factory canteen, furniture removals, students’ union, Dunnes, Argos, lecturing at NWRC and in other newspapers, coming back to the Journal still felt like coming home.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI’d like to thank all the staff, past and present, who have contributed to this special edition. It hasn’t been easy in the middle of an office move, and with a much smaller team than we had back in those days of the huge Friday Journals, but their stories, their efforts underline the sense of pride and kinship among people who have worked at the Journal feel.

And there’s a sense of ownership among the readers too. This is your paper and your website every bit as much as it is ours. We have been telling your stories and the story of Derry, Donegal and the wider north west for 250 years. Thank you to all our readers and advertisers for trusting us, and for helping us to support and inform our community over the years, and as we enter a new era in our new office on the first floor of the Catalyst building at Fort George, let’s hope we can continue to do so for generations to come.

Print copies of the special 250th anniversary edition can still be purchased online for a few more days and can be posted worldwide. See www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/derry-journal-250th-anniversary-edition-tickets-324902330617