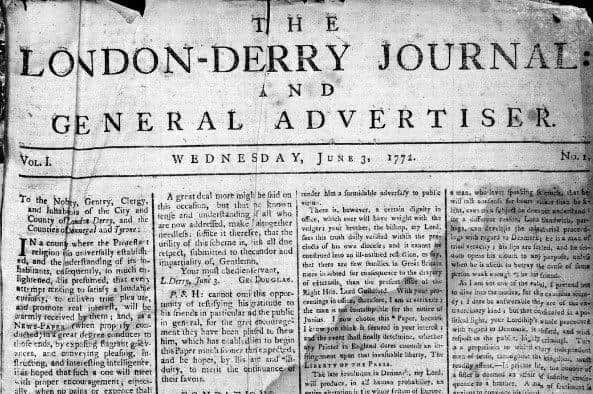

DERRY JOURNAL 250: What kind of Derry was the ‘Journal’ reporting on the day of June 3, 1772?

and live on Freeview channel 276

The civilian population had grown from 2,349 in 1660/1 when it was bigger than Belfast (pop. 1,708) to 9,313 in 1821, so when the ‘Journal’ first appeared on Wednesday, June 3, 1772, Derry was about as populous as Buncrana is today.

Physically the city would have looked quite different, particularly in and around the 17th century City Walls which would have been the centre of civic life at that time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSt. Columb’s Cathedral, the Bishop’s Palace and several buildings around Shipquay Street, London Street and Pump Street, are among the only survivors from the pre-‘Journal’ era in the city centre. The familiar grid system, laid out in the 1600s during the Plantation of Ulster, is also extant.

In 1772 a bridge had yet to be built. Arthur Young, the English farmer and writer, who visited Derry in August 1776, in his ‘Tour of Ireland’ recounts reaching Derry at night, and waiting ‘two hours in the dark before the ferry-boat came over for me’.

It wasn’t until 1789 that Bostonian bridge builder Lemuel Cox was asked by the Corporation to build a span across the Foyle. It was eventually completed and opened to foot passengers in 1791.

The development was the culmination of a twenty year campaign for a bridge by the city’s civil leaders. The Corporation was supported by the legendary Earl Bishop Frederick Augustus Hervey and opposed by James Hamilton, the 8th Earl of Abercorn whose ‘big house’ was at Baronscourt near Newtonstewart. The merchants of Strabane were also minded against a bridge in Derry as inimical to their interests.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter building the Charlestown bridge in Boston and the Essex bridge in Salem, Cox was invited to Derry.

DERRY JOURNAL 250: First editor George Douglas’ ‘Journal’ reported on a time of revolutionary ferment“In 1788 he sent over a model of the bridge (which was to be built with American oak, his favoured wood), and various parts and workmen were also brought over. On May 3, 1790 building commenced on the project, which, when completed, was 1,068 ft (325.5 m) long and 40 ft (12.2 m) wide.

“The bridge took thirteen months to complete, at a cost of £16,294. In 1792 Cox himself came to Ireland, bringing his wife and sons Lemuel and William, and received numerous commissions to work on bridges,” the Dictionary of Irish Biography explains.

To get a sense of what the city looked like in the 1770s it’s possible to refer back to Young who visited on August 8, 1776 during his trip around Ireland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The view of Derry at the distance of a mile or two is the most picturesque of any place I have seen. It seems to be built on an island of bold land rising from the river, which spreads into a fine basin at the foot of the town; the adjacent country hilly. The scene wants nothing but wood to make it a perfect landscape,” he wrote.

Not so different from the view of the city as it is approached today, especially from Killea and Newbuildings to the south.

In the 1770s the population continued to grow thanks to a boom in the flax trade. Derry Presbyterians who had emigrated to the American colonies throughout the 1700s and set up base in Philadelphia established strong trade links with their ancestral home.

The Dublin-based historian David Dickson, who happens to have close connections in Fahan, in his 2021 study, ‘The First Irish Cities: An Eighteenth Century Transformation’, writes: “From the beginning, the Presbyterian districts of the north-west had shown a heightened propensity to emigrate, although it was only from the 1740s that the movement became regular, closely complementing the reverse flow of flaxseed from the Middle Colonies in which Derry’s merchants also invested, making the best of both opportunities. Given Derry’s remote location, a high proportion of the shipping was locally owned (some 67 sea-going vessels in 1767, compared to ‘about 50’ in Belfast), and the trade was largely conducted on local Derry account, although there were close business links with kin and co-religionists in Philadelphia’s merchant community including some Derry investment in American-based vessels.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDERRY JOURNAL 250: It did indeed prove to be a ‘job for life’The 1770s was a time of increased emigration, and by Presbyterians rather than Catholics. This was intimately connected with linen and flax.

Young recorded: “The spirit of emigration in Ireland appeared to be confined to two circumstances, the Presbyterian religion, and the linen manufacture. I heard of very few emigrants except among manufacturers of that persuasion. The Catholics never went; they seem not only tied to the country, but almost to the parish in which their ancestors lived.

“As to the emigration in the north it was an error in England to suppose it a novelty which arose with the increase in rents. The contrary was the fact; it had subsisted perhaps forty years, insomuch that at the ports of Belfast, Derry, etc., the passenger trade, as they called it, had long been a regular branch of commerce, which employed several ships, and consisted in carrying people to America.”

Emblematic of this era of emigration was the tragic end of the ‘Faithful Steward’ which left Derry for Philadelphia in July 1785 with a cargo of 249 emigrants and 400 barrels of copper half pennies and rose gold guineas on a voyage to the revolutionary United States - the American War of Independence (1775-1783) erupted not long after the ‘Journal’ published its first number.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe ship foundered near the mouth of the Indian River in Delaware just yards from shore and only 90 miles from Philadelphia. All but 68 of the 249 emigrants were drowned. There is a granite bench memorialising the ship down behind Sainsbury’s.

By the time this paper’s first edition hit the streets Derry was thriving thanks to the flax and passenger trade.

As Dr. Dickson notes: “On the strength of the American trade Derry moved from being something of a backwater in the 1720s to a wealthy port by 1770 drawing its human cargoes from a wide swathe of West Ulster and, in reverse, distributing the flaxseed across half the province. The other element in its prosperity was linen yarn, almost all of it exported on the ‘yarn ships’ to Liverpool. This trade had grown from almost nothing in 1700 to be worth at its peak in the 1760s, over £100,000 [over £21m in today’s wee plastic notes] (straining the capacity of small Ship Quay, despite improvement grants received from the Irish Parliament).”

Dr. Dickson suggests the patronage of one particularly powerful politician may have done Derry’s trading community no harm.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPrivy councillor, revenue commissioner and firm defender of the Protestant Ascendancy John Beresford, who was dubbed the ‘King of Ireland’ wielded extensive political power and influence. Beresford had a ‘big house’ in north Derry and was a relation of Hugh Hill, the mayor of Derry in 1772. Whatever his influence trade was boomy.

DERRY JOURNAL 250: Breaking the Journal’s glass ceiling!It is worth quoting the ‘shipping news’ from the very first edition of the ‘Journal’ to get an idea of the extent of Derry’s trade links at the time.

“Arrived. May 23, The Isabella of Campbeltown from Liverpool, McKinly, master, with White Salt and Earthen Ware - 26. The Everton of Londonderry from Liverpool, McConnel, master, with Rock Salt, Tobacco, &c - 28. The Endeavour of Yarmouth from London, Cooper, master, Tea, Spirits, Porter, &C - June 1. The Symmitay, Foxton, Mimil, Timber; The Sally, McCliland [sic], Dominica, Rum and Sugar - 2. The Swift of Londonderry from Air [sic], Feeny, master, Coals.

“Cleared Outwards. May 23, The Susie of and for Glasgow, Hunter, master, Ballast - 23. The Countess of Inchiquin of Cork, for Air [sic], Buck, master, Ballast. The Diligence for Bristol, Meredy, master, Flax Seed and Ballast - June 1. The Jennies of Campbeltown for Bergen, Curry, master, Tobacco and Ballast; the Dispatch of Londonderry for Bristol, master, Kelp and Ballast.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAn advertisement placed for a Richard Caldwell, a merchant of the city, offers a range of exotic goods from around the world on the lowest terms.

The inventory includes: “Druana Raklitzer Flax, Jamaica Spirits, Grenada Rum, Muscovada Scale Sugar, Brandy, Geneva, Florence Oil, Smalts of the finest quality, Oil of Vitriol, American Pot and Pearl Ashes, Weedashes, Best Sweet Barilla, Black Soap, Best French Indigo, St. Ubes Salt, Flat and Square Bar Iron, Steel in Bars, Madder, Liquorice Ball, Jordan Almonds, Gun-powder, Linseed Oil, Whalebone, Writing Paper of Sorts, Madeira Wine, Old Hock and Seltzer Water.” All you could want for the weekend.

Derry remained a garrison city in the late 18th century, politically controlled by the Protestant Ascendancy, however construction of a new Catholic chapel at the Long Tower began in 1783.

It was built near a hawthorn which was reputedly the site of Colmcille’s Teampall Mór, the great cathedral of the original monastic settlement of Doire Colmcille, founded in 546. The church was completed in 1788.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter the reversals of the Nine Years’ War and the Plantation in the early 1600s the native Irish of Derry had then to endure the indignities of the penal laws. These included the Education Act (1695) that prohibited the Irish from sending their children to Europe to be educated; the Banishment Act (1697) that sought to banish Catholic clergy - an important leadership cadre for the native population - from Ireland entirely; and the Registration Act (1704) which required any ‘Popish’ priests to register with a local magistrate and to pay a bond on good behaviour.

To the harried populace the Mass rock was their place of worship and the hedgerow their classroom.

To continue practising the Catholic religion had had lethal consequences for some as Friar Séamus ‘James’ O’Hegarty found out when his head was cut off by an English officer named Vaughan in Buncrana in 1711.

Many priests, unable to train in Ireland, went off to the seminaries in Europe. Fr. John Lynch, a native of Balteagh, Dungiven, was one such priest. He was a graduate of the Sorbonne in Paris.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDERRY JOURNAL 250: ‘To the Nobility, Gentry, Clergy, and Inhabitants...’ The very first Derry Journal, June 3, 1772Prior to the erection of the new Long Tower chapel Fr. Lynch had been used to saying Mass in his house in Ferguson’s Lane, or at the hawthorn tree which marked the site of the Teampall Mór. It was Fr. Lynch who set about raising funds for the new church.

It is notable he received 200 Guineas from the Protestant Earl Bishop Hervey, who was among a growing number of supporters of Catholic emancipation from within the Ascendancy.

Derry, a bustling trade post and port, was now attracting migrants from its hinterland and Scotland. The burgeoning Catholic population - including newcomers from Donegal and the Sperrins - was growing outside the walls.

A survey conducted in 1738 had found there were very few cabins - single storey buildings with mud walls inside the walled city. But 275 out of 330 houses outside the walls were of this type. In the decades after the publication of the first ‘Journal’ the Catholic population of the ‘cowbog’ - the location of the Bogside today - to the south and west of the Walls would rapidly expand.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLiving conditions would have been poor, often squalid, and mortality and morbidity obviously much higher than today.

Dr. Dickson in ‘Irish Cities’ observes: “In Derry in the first half of the eighteenth century infant and child burials regularly made up two thirds of all interments, the proportion occasionally flaring up some seasons to 90 per cent, reflecting the lethal impact of smallpox and more occasionally, influenza and measles epidemics.”

DERRY JOURNAL 250: ‘The wee girl from the Journal’Things are unlikely to have improved by the latter half of the century. When the first copies of the ‘Journal’ were printed there was no reservoir. The city would wait until 1808-1809 for the construction of a facility at Corrody. This involved the construction of stone-faced embankments with a puddle clay core to prevent the seepage of water which was conveyed in wooden pipes to a tank at Fountain Hill in the Waterside and Fountain Street on the cityside.

Metal pipes were used to transport the water across Lemuel Cox’s wooden bridge. Before the Corrody reservoir was created there would have been a great dependence on the wells and springs of the city including St. Columb’s Wells, where three wells were situated and a well at Bishop Street at its junction with London Street.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGeorge Walker, the Governor of Derry during the Siege, just under a hundred years prior to the ‘Journal’s first edition, wrote: “The shortage of unpolluted water was one of the greatest hardships of the Siege. Approaches were made to our line designing to hinder relief of our guards and give us trouble in fetching our water from Columbkill’s Well.”

William McKee, Western Divisional Manager of the Water Service, writing in 1979, explained how various experiments were carried out on the ‘spa, pump and spring waters of the city’ in the 1790s and early 1800s.

“In 1788-89, the experiments related more to the temperature of the water in the wells and springs, whereas the 1802 experiments were more detailed. Those sampled were: Bishop Street town pump (1788, 1789, 1802); Pump in Bishop’s Garden (1788); Spring on the west Strand (1788); Old spa well (1788, 1802); Riverlet near town of the west Strand, (1788); Pump in Eddy’s Lane, now Richmond Street (1789, 1802); Rosses Bay (1802); Pump at Poor House (1802); New Pump at Ferryquay Gate (1802). The experiments carried out in 1802 appear to have fallen into three main categories - 1, To test the presence of iron; 2, To test for hardness; 3, To test for acidity or alkalinity.”

Citizens, it appears, have been enjoying the ‘Journal’ longer than they have had a steady water supply, the ablility to walk or wheel their ways across the River Foyle on a bridge or access to a permanent Catholic place of worship, among other things.