Author recalls horror faced by WWI relative

By the time James McGonagle went to war, his younger brother, Charles, was already entrenched in the excavations that polluted and pock marked the fertile fields of Flanders and France.

The brothers had been born in Derry but, as both parents had died some years previously, they treated Owey Island, in Donegal, as home. This was the home of the family of their mother, Annie, and where their older brother, Owen, was a fisherman.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCharles had enlisted before war was declared but James had the benefit of five months of daily reporting in newspapers and, therefore, knew something of the dire situation at the front, of the battles, of life and death in the trenches. His motivation may have been different in some respects from his brother but must have been strong enough to counter knowledge of the realities of the war. James enlisted shortly before the death of his brother, Charles, was reported.

Charles McGonagle had left his island home, arriving in Derry in the hope of employment, but without a specific skill, such as brick-laying or plumbing. He remained unemployed in spite of the city’s then buoyant economy.

Like other young unemployed men, Charles could have spent his abundant free time learning to play the game of soccer with former members of the Derry Celtic team in their ground at Celtic Park, not far from his Lecky Road home. When not actively engaged playing football, he could inform himself about local conditions and about the fraught politics of the times.

There were now Irish Volunteers, Ulster Volunteers, and volunteers for the army to confuse and annoy the citizenry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMilitary drilling by the Irish Volunteers was carried out in Celtic Park on St Patrick’s Day 1914. The assembled crowd enjoyed the marching and the general military rigmarole. They heard speeches about the aims of the Irish Volunteers: to secure and maintain the rights common to the whole people of Ireland, and also that they were a defensive, not an offensive, organisation.

By the end of September 1914, there were 9,400 Ulster Volunteer members in County Derry. Irish Volunteers numbered 7,405, and were much less well armed. The declaration of war by the British on Germany on August 4, 1914 may have prevented the clash of incompatible forces on the island of Ireland. By February 15, 1915, 23,300 Ulster Volunteers and 20,000 Irish Volunteers had enlisted in the British Army. Their energies would be expended on the Western Front rather than on the fields of Fermanagh.

It was on the morning of March 18, 1914, that Charles McGonagle joined the 1st Battalion, Irish Guards Regiment of the British Army. With admirable swiftness and precision, the sergeant at the desk recorded his physical and personal details: height and weight were measured, colour of eyes and hair, religion, next-of-kin and distinguishing marks were entered under his name and address.

Charles joined the sergeant’s line and received his shouted orders to, ‘Quick march’. To cheers and echoing brass, they formed up beside Derry’s Walls, then they strode proudly into Foyle Street and along John Street; they broke their stride across Carlisle Bridge and marched on to Ebrington Barracks in the Waterside.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA career in the army was a kind of employment, after all, that would provide a steady income of one shilling a day for a private soldier and the chance to send some money to his island family. A curious and effervescent young man could make good friends and find exciting things to do in an army.

During rudimentary training at the depot at Warley, Essex, recruits enjoyed both the strenuous physical and technical aspects of the process of becoming fighting men. It was here that the recruits formed their brotherhood, a loyalty to each other that would at least match that to King and Country. Overwhelmingly Irish and Catholic, they got to know their priest chaplains who failed to modify their capacity for certain kinds of stories and use of language their mothers never knew, and could never contemplate, that their sons used.

On Sunday, August 9, 1914, the 1st Battalion the Irish Guards marched to Westminster Cathedral for Mass and a sermon by Cardinal Bourne who reminded them of the ‘Wild Geese’ of history and legend who fought side-by-side with the French in earlier, violent times. A few days later, at Wellington Barracks, the Colonel-in-Chief, Lord Roberts, in full dress uniform of scarlet, with sword and ostrich feathers, bade them farewell. He explained that certain events in Europe had brought war and that they were deployed to France to resist German aggression against small nations. The ritual send-off was impressive. It was reported that someone whispered: ‘They say it will all be over by Christmas’.

On the warm, dull day that was Wednesday, August 12, the band played the slow regimental march, ‘Let Erin Remember’, as the crowded vessel, the SS Navara, cast off from Southampton, eased herself out of the Solent, and into the Channel. Off Ryde, on the east coast of the Isle of Wight, signals were exchanged with the great battleship HMS Formidable and the band played ‘Daisy, Daisy’, accompanied by over a thousand tenors, baritones and basses.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNot having rested during the night, the mixture of emotions showed as the battalion struggled down the gangplank. Being entirely in the care of the military authorities meant they didn’t have to think as individuals when first meeting the residents of Le Havre, who insisted on speaking French.

It was hot at Le Havre. They bathed in the sea to brighten themselves up, but, when the weather broke and torrential rain soaked the new uniforms, they looked as if they had been bathing fully clothed.

The approach to the front was long and tedious and the men were happy to eventually dismount from the rickety transports that rattled and shook their ‘in’ards’ over cobbled highways. They marched the final miles and heard shelling not far away to the east. In silence, they viewed their billets for the first time. Already they saw a contrast between the optimism and frivolity of the send-off and the reality of this strange, bleak, noisy land without birds or flowers. Enthusiasm turned to fear.

Within a few days, on August 23, the Battalion advanced at Mons and participated in the bloody Great Retreat there the following day. Later, they advanced at the First Battle of the Marne and at the Battle of Aisne. They fought the First Battle of Ypres, from October 21 to November 11, losing huge numbers during the first week of November while defending Klein Zillebecke.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy late autumn, seven hundred casualties had been recorded. They learned what it was like to be shot at, to be shelled, and to go without food for days at a time; they learned to pick up their wounded and bury their dead. Already, a kind of warweariness began to stab at young hearts.

At Bethune, on Christmas Eve 1914, Private Charles McGonagle enjoyed plum pudding and the occasional artillery bombardment. On Christmas Day, two officers and six men were wounded. The battalion had now become accustomed to some such disturbance daily. Across no-man’s-land, they heard the Germans singing and playing mouth organs. A tenor sang Shubert’s ‘Ave Maria’. They never knew whether he was German, French or Irish.

For days, they did their best to survive the cold and the wet, the mud and the horrors of finding their friends dead beside them, as ever-vigilant snipers did their deadly work for Kaiser Bill.

On January 30, they moved up to Cuinchy, where they found the old trenches ‘not very wet but otherwise damnable’. They were uninhabitable. Having been taken and lost several times, the trenches had crumbled and collapsed in many places. In the bottom, corpses of both German and British origin remained, too far-gone to remove in one piece.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe nearby canal heaved with rats at night as they came up to feed on the carcases in the trenches. It was here that an officer, on hearing a noise on his bed in a dugout, removed the blanket only to find two rats fighting over a severed hand.

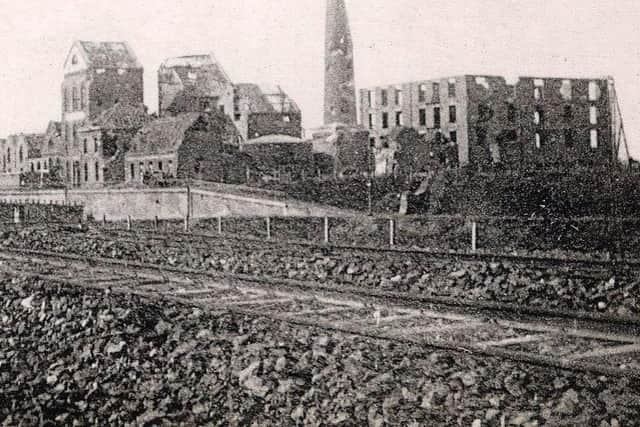

At Cuinchy, huge stacks of bricks sheltered the Germans at one end, the British at the other. Attempts had been made to line the bottoms of the trenches with bricks but they made little difference; the men preferred to remain among the stacks where shelling and sniping made for great danger.

At 4 am on February 1, 1915, Charles McGonagle’s Company was ordered forward, led by Robert St John BlackerDouglass. Blacker-Douglass was injured by a grenade and later shot through the head and killed. Lance-Corporal Michael O’Leary, from Cork, attacked and destroyed two machine-gun posts with such ferocity and courage that he was later awarded a Victoria Cross. Shelling of the positions among the stacks continued. They counted one officer and six other ranks killed. Twenty-five men had been wounded since their arrival at the stacks.

Sunday, February 14 started very busy indeed. With the dawn came a British artillery bombardment of the Germans until 10.05 am. In return, the Germans bombarded the trenches, destroying yet more of the structures. At 11.30am, a message of optimistic tone was received, confirming that the French advance nearby had been successful. A short time later, two men were killed: one was Lance Corporal Michael Carey, from Limerick, aged 29; the other was Private Charles McGonagle, from Donegal, aged 20.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOver the next couple of months, a number of letters arrived at the home of Joseph McGonagle, on the Lecky Road, Derry. Both Charles and James had named Joseph as next-of-kin, their father, Stephen, and mother, Annie, having both passed away some years previously. In a routine military expression of regret, the first letter, from the Commanding Officer, Major Trefusis, carried sincere sentiments that Private Charles McGonagle had died in the service of his King: ‘Deeply regret to inform you that Private C. McGonagle Irish Guards was killed in action on 14 February. Lord Kitchener expresses his sympathy.’

The brief note marked the end of a brother’s young life. A later communication included three medals due to the dead soldier: the 1914/15 Star, the Victory Medal and the British War Medal. Medals that Charles would never see or wear and that were to be put aside for very particular reasons.Later, the Imperial War Graves Commission wrote with details of the location of Charles’ burial in a windy corner of France.

NEXT WEEK: the story of James McGonagle.