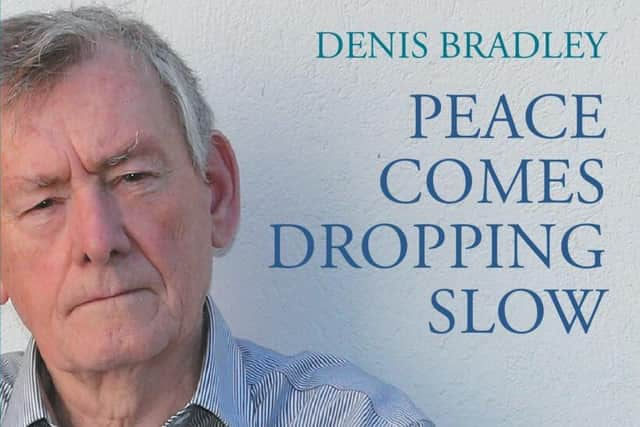

Denis Bradley memoir a frank account of the journey from conflict to peace

and live on Freeview channel 276

It was 1993 and a ‘backchannel’ link between the republican movement and the British was in danger of collapse.

Brendan Duddy had suggested Mr. Bradley take the British operative to Martin McGuinness’ mother house to talk to the Sinn Féin leader and try to salvage the situation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"When McGuinness opened his mother’s front door that night in March 1993, and before he could say anything, I told him that Robert McLarnon, more frequently referred to by his MI5 code name Fred, was in my car, which was parked farther up the street.

"I was amazed that Fred had agreed to go with me into the heart of the Bogside where he could have been abducted and used for ransom,” Mr. Bradley writes.

Mr. McGuinness gave the former priest a look as if to say, ‘You are chancing your arm again, Bradley’ but ‘Fred’, McGuinness and Gerry Kelly, who was in the house watching TV with Peggy, had their tête-à-tête.

"I knew that if this meeting didn’t go ahead, then it could be the end – the end of almost twenty years of hard work to make it to this point, the end of potential talks between the British government and republicans...twenty minutes later McGuinness opened the kitchen door and nodded to me. The meeting was back on,” Mr. Bradley recalls.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad‘Peace Comes Dropping Slow: My Life in the Troubles’ will be required reading for anyone interested in recent Irish history and current affairs. It comes from the pen of someone who enjoyed a unique vantage point as the Troubles erupted and peace unfolded in Derry over the past 50 years.

Mr. Bradley rubbed shoulders with and was often a confidant or acquaintance of figures including John Hume, Martin McGuinness, Eddie McAteer, Stephen McGonagle, Bishop Edward Daly, Fr. Anthony Mulvey, Fr. Tom O’Gara, Ivan Cooper and many others.

He was a member of the aforementioned ‘backchannel’, which acted as go-betweens for the IRA and the British government, and also served as the first vice chair of the Policing Board.

Perhaps one of his most important roles was the establishment of the Northlands Addiction Centre, which has provided support to so many citizens who have struggled with drug and alcohol dependency in Derry over the decades.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAll of these aspects of his life are covered in depth in ‘Peace Comes Dropping Slow’.

After the tense prologue the memoir begins, however, with personal detail. Mr. Bradley tells the reader how he is ‘one of those northerners who wasn’t born in the North’.

He recounts his early life in Buncrana where his mother ran a guest-house and his father drove a Lough Swilly bus. His people were from the Illies.

His father was a ‘quiet, gentle man’ whose strongest political opinion had been that he was death on poitín due to the corrosive effects he had witnessed the spirit having on the working men of rural Inishowen.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen he set up the Northlands in Derry Mr. Bradley remembers being asked about the reason for his involvement.

"It was sometimes insinuated that I had personal or familial experience and I had, but not in the way people thought. Being a well-built young man with broad shoulders, my father was often called upon to go out into the bog and carry men home over his shoulders to their wives and children.

"He described scenes of very drunk men huddled around, drinking poitín as it dripped out of the still,” he writes.

During these days Mr. Bradley was no stranger to Derry and went to school in the city in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"I ended up as a boarder in St Columb’s College in Derry. It was big and cold and the food so bad that I was hungry for the greater part of five years.

"There was an underlying homesickness, but I was not always unhappy there. I made good friends, and it enabled me to grow a resilience that I think helped me in later life,” he writes.

He was to train to be a priest at Maynooth and was due to start at the seminary in September 1964 but in a stroke of good fortune was sent to the Irish College in Rome instead.

There were about sixty students at the Via dei SS. Quattro.

"Small was beautiful for a shy young fellow, although I felt like I was going to die of homesickness in my first two weeks there,” he reflected.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring his stay in the ‘Eternal City’ he became influenced by the writings of US social activists Dorothy Day, Cesar Chavez, Saul Alinsky and Daniel and Philip Berrigan.

Six years later he returned to find his home city in a state of political ferment.

“When I arrived back in Derry from Rome in 1970, the civil rights movement had been the dominant issue in politics, and on the streets Martin Luther King was the name and the inspiration known to all and sundry, especially in the Catholic, nationalist community,” he recalls.

He said he was surprised the names of Day, Chavez, Alinsky and Berrigan were not on the lips of those marching on the streets of Derry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter attending a Catholic Social Action Conference in Waterford addressed by John Hume he drove back up the country with the future SDLP leader.

"I gave him a lift back to Dublin and talked to him about the American social activists that I had read about while in Rome, and, again, was greatly surprised that he was not familiar with any of them.

"Hume was fast becoming known on the national and international scene, but his initial activism was in helping establish the Derry Credit Union, one of the most beneficial and lasting social movements of the time,” he recalls.

Upon arriving back in Ireland he feared he would receive a rural posting.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"It was a relief when I got a phone call telling me that I was going to help in the cathedral parish in Derry for the summer months. The cathedral was situated right at the heart of what was happening on the streets of Derry, and I was very happy to be given a summer placement there,” he relates.

But he later found himself being transferred to the Long Tower after an alleged clash with Fr. Benny O’Neill, administrator of the cathedral.

“One evening, as the five of us [Frs. Tony Mulvey, Eddie Daly, John McCullagh and Bradley] sat around a dinner table, O’Neill, as he was wont to do, was excoriating the rioters of the previous night as being hooligans or communists or something of that ilk.

"As he was in full flight, Daly claimed, a voice that came from the bottom of the table said, ‘Benny, that is a lot of crap.’ Daly said that, apart from nearly choking on their chicken or whatever they were eating, the three curates knew that after that my days in the cathedral were numbered and I would be banished to some less auspicious parish.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"I don’t recall the incident and it is possibly apocryphal, but I do remember the three curates becoming more open and warmer to me,” he recollects.

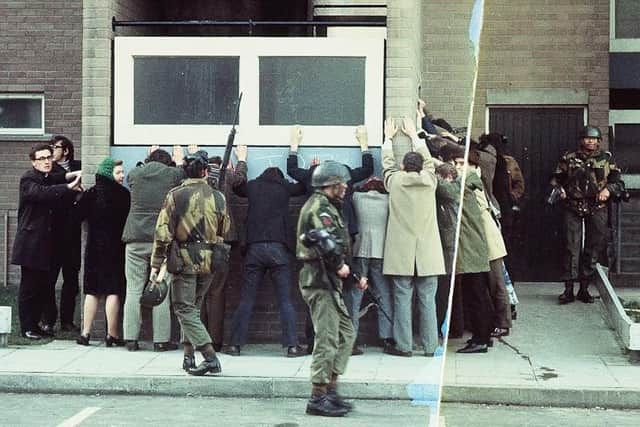

Mr. Bradley was an eye-witness as the situation on the streets deteriorated in the early 1970s.

He remembers a marked increase in tension after Seamus Cusack (28) and Desmond Beattie (19) were shot dead by British soldiers on July 8, 1971.

"From that time on, you could almost see the thing escalating and sense that more and more people were going to be shot. The tension, bitterness and recrimination heightened with every killing,” he states.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdInternment, introduced in August 1971, poured fuel on the flames.

His first direct encounter with violent death as a priest was when Billy McGreanery was shot dead by a member of the 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards on September 15, 1971.

“I still remember the anger I felt. I would have been angry enough at Billy’s death, but to hear a public announcement that described him as a gunman who had been shot dead because he was shooting at the army left me feeling outraged.

"I didn’t know everyone who was in the IRA, but I knew who was not in the IRA. Billy McGreanery was as likely to be in the IRA as I was,” he fumes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBloody Sunday, to which Mr. Bradley was a personal witness, receives a chapter of its own.

He recounts walking to William Street after celebrating baptisms in the Long Tower shortly before the massacre began and remembers the Paras moving into Glenfada Park.

"Big, aggressive men with blackened faces. One kept shooting, spraying bullets indiscriminately. They appeared surprised to see the group of us huddled against the wall and ordered us to put our hands on our heads and walk towards William Street.

"One of them kept shooting and as I grabbed his arm to stop him, he threw me to the ground. It was only then I noticed other bodies lying on the ground in the park,” he shares.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe book goes on offer reflections on Operation Motorman, the hunger-strikes and many other pivotal events in the evolution of the conflict and on the road to peace.

Mr. Bradley’s account of his role as a key conduit of the ‘backchannel’ between the IRA and the British Government first established in the early 1970s is illuminating.

It comprised, he writes, of the author, the late Brendan Duddy, and Noel Gallagher, a former national organiser with Sinn Féin from the Bogside, and it was first instigated by the respected local superintendent of the RUC Frank Lagan.

“This backchannel, as it came to be known, wasn’t established in any planned, formal manner. In fact, serendipity played a large part. Frank Lagan was talking to Duddy on a regular basis, Duddy regularly talked to me, I talked to Lagan, and Duddy and I talked to Gallagher,” writes Bradley, who for the next twenty years helped facilitate an engagement between the two sides that is credited with ultimately facilitating peace and the Good Friday Agreement.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe link foundered in the 1970s but had been revived by the time Bradley turned up at Peggy McGuinness’ house in Cable Street with ‘Fred’ in the car in 1993.

The fascinating memoir offers a frank assessment of the difficulties in establishing a new police force in the early 2000s and the personal attacks Mr. Bradley was subjected to after he became vice-chair of the Policing Board.

This culminated in a brutal baseball attack in a pub in the Brandywell that left him hospitalised in 2005.

Dissident republicans has been ‘bold enough to attack my home on a few occasions and bold enough to hit me over the head with a baseball bat in a pub one evening when watching a football match with my youngest son’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMost intriguing are Mr. Bradley’s candid insights into the tensions in the personal relationships between some of the most significant players in our local history over the past half century and more.

‘Peace Comes Dropping Slow: My Life in the Troubles’ by Denis Bradley, is published by Merrion Press and is available online at https://www.irishacademicpress.ie/product/peace-comes-dropping-slow-my-life-in-the-troubles/ and in all good bookshops.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.